Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 38 Issue 8

Author: Dimitris Symeonidis

Turkmenistan, together with the rest of Central Asia, has been touted by many as the energy powerhouse both of the present and the future. Its natural gas reserves place it on the 6th position globally, accounting for 4% of the world’s reserves, whilst its abundant wind and solar power capabilities, due to its vast amounts of land, make it a potential future clean electricity and hydrogen hub.

This has been recognised by virtually all external global actors, including China, the EU and India, all of which have developed or attempted to develop energy partnerships in an effort to satisfy their demand-hungry economies and escape from energy insecurity.

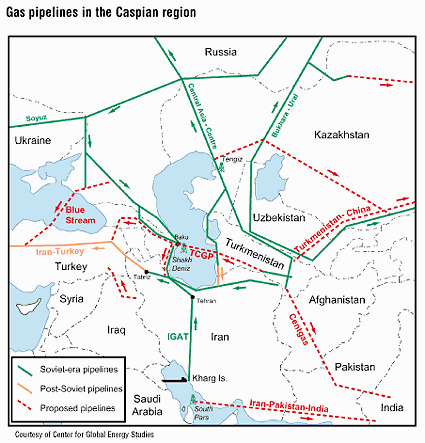

Out of the foregoing actors, only China has managed to materialise its plans, through the China-Central Asia pipelines. The other two projects, namely the TAPI pipeline and the Trans-Caspian pipeline have only remained at concept level so far. The reason in both cases is a combination of lack of funds and political will.

In the case of the Caspian Sea, the main backlash over alleged environmental concerns comes from the Russian side, whereas in the TAPI pipeline there is lack of support and recognition over the legitimacy of the Taliban regime.

Reflecting on the difficulties, a third solution might emerge, looking westward into the Middle East and it passes through Iran and Iraq.

Despite the fact that (geo)political issues make this alternative also a faraway dream, Ashgabat has already initiated partnerships with Baghdad and Tehran, focusing on gas swap agreements and electricity trade, and based on these developments and future prospects, this electricity and energy diplomacy could have potential to evolve into a long-term peacebuilding project for the Middle East and an energy security project for Europe.

Taking this into consideration, it presents great interest to examine these relationships and analyse them further under the prospect of a regional pipeline project.

The existing conditions cannot be considered as the best ones for an energy investment that connects the three countries and provides them access either directly to Europe or to LNG terminals. Nevertheless, progress has been made in the relations between the three nations, as well as with external actors, that show a promising future for a prospective Turkmenistan-Iran-Iraq natural gas connection.

Exploring Bilateral Relations

- Turkmenistan-Iran. The relations of Turkmenistan and Iran have a considerably long history and span across multiple sectors. Considering the vast natural resource reserves of both, it is safe to assume that energy is on the top of their collaboration agenda, together with transport of goods and industry.

More precisely, Iran’s imports from Turkmenistan account for 55% of the total imports which tally up to $5.5 million, whilst Turkmenistan’s imports from Iran are around $400 million, out of which 25% are minerals. The reason for the disproportionately larger share of energy exports from Ashgabat compared to Tehran is that the latter has a much larger heavy industry than the former.

The main piece of infrastructure used for energy trade so far has been the Korpeje-Kurt Kui gas pipeline, which transports gas from the northern part of Okarem in western Turkmenistan to the city of Kordkuy in northern Iran. The total capacity is of 8bcm/year and the main purpose for its construction has been to support the northern part of Iran, which is remote and highly industrialised.

In addition, in 2010, Ashgabat commissioned a 182-kilometer pipeline going from Dovletabad to the Khangiran gas field in northwest Iran. However, both pipelines have not been operating in its full capacity and that is also why Ashgabat and Tehran signed a series of gas swap agreements, with the end goal being that Iran imports from Turkmenistan up to 10bcm/year, looking to re-sell them to Azerbaijan as part of a trilateral gas swap agreement.

The relations between the two neighbouring states have been through various phases, as turbulence has also existed in several occasions. Some of them include the suspension of gas exports from Turkmenistan following the death of President Niyazov in 2007, a ceasing of gas trade in 2017, but also a similar occasion that occurred this year due to technical issues that had taken place from the Turkmen side.

Another reason for the disruptions has been the debt that Asghabat maintains towards Tehran. However, despite the aforementioned disruption, the past 5 years have been characterised by an effort from both sides to bridge the gaps and increase their energy trade, but also expand to other markets and formulate an alliance for exports to demand-hungry regions like Europe.

Considering the limited exporting capacity under the current pipeline and LNG network, it would be useful to explore other partners to form trilateral or multilateral frameworks, the most convenient of which would be neighbouring Iraq. - Turkmenistan-Iraq. The interactions between Turkmenistan and Iraq have been scarce up to this date. The presence of Turkmen minorities in Iraq has been the primary source of interactions, as these populations have held strong ties with Iraqi citizens, working as a link between Arabs and Kurds.

However, at a diplomatic level, there have been very few consultations, the last of which in 2017 to discuss collaboration on countering terrorism. This used to be the case until October, 2023, when the two countries agreed on a gas trade deal, according to which Turkmenistan would supply Iraq with 9bcm/year via the Iran-Iraq existing pipeline infrastructure. The main rationale behind this move is that Baghdad, despite its position as the 12th richest nation in natural gas globally, does not have the necessary funds for extraction, nor the necessary technology to take advantage of the gas flares that oil fields produce.

Efforts had been made to increase the total capacity of the aforementioned infrastructure, such as through adding the Iran-Iraq-Syria pipeline, also known as Friendship Pipeline, however such plans have not materialized to this day. One way to attract investment and bring stability, both to Baghdad and the region, have been joint projects of common interest, which include, but are not limited to, energy production projects and pipelines. - Iran-Iraq. Following the war between Iraq and Iran that broke out in 1980 and didn’t stop until 1988, the relations between the two nations have been constantly ameliorating. In the landscape after the US Iraq War, in particular, after 2005, the two countries have become very strong allies and Tehran has become Baghdad’s biggest trade partner.

The first set of discussions on oil & gas trade, nonetheless, took place in 2010, as a swap agreement was discussed, which aimed at Iran exporting natural gas to Iraq in exchange for crude oil as well as fuel oil flowing towards the opposite direction. This arrangement was finalized at 2017, but was faced with numerous disruptions in the following years, predominantly because of the indebted situation that Iraq is with regards to Iran.

It should be noted that this agreement was not the first one on the energy sector, as Tehran has been supplying Baghdad with electricity, with figures starting from 1 billion kWh in 2006 and rising up to more than 6,5 billion kWh in 2020.

Common Patterns

Reflecting on the relations between the three state actors, it is paramount to find common patterns on challenges they have faced and successful collaborations, so that a strategy towards a successful trilateral cooperation framework can be formulated.

- Debt flows from Iran to Iraq and Turkmenistan. Both countries have faced issues in the past, which would be the biggest impediment if a financial cooperation for larger energy flows is to be solidified. Considering also that such a cooperation would require investments in relevant infrastructure, it is important that all partners delineate financial sustainability.

- Political stability and will. The Middle East has been characterised by turbulence, both in the relations of Iran with the EU and the US, but also in the internal stability of Iraq and other state actors that might prove to be crucial for the uninterrupted energy flows of the envisioned project, such as Syria.

- The global perception of the aforementioned state actors. Stakeholders like the EU and the US are reluctant in engaging with all three countries for political and financial reasons.

- Existing pipeline infrastructure is both outdated and it is not being used to its fullest extent. This, on one hand, opens ample opportunities for further natural gas trade. However, it also creates concerns about what would happen if these flows increase and it adds a need for further maintenance of the foregoing infrastructure and potentially expansion with new set of pipelines and, perhaps, even LNG terminals, if the path through the Persian Gulf is deemed as the most financially and politically sound solution.

Taking the aforementioned into consideration, a plan of action is needed to overcome the obstacles that inhibit the three nations from pursuing a common energy agenda. In this regard, neighbouring countries, as well as external actors, with access to capital, diplomatic capabilities and direct access to demand-hungry markets can pose as serious allies and need to be analysed further.

The Role of External Actors

As mentioned, external actors in the immediate neighbourhood can bring immense value and boost the implementation of a project that will help the region develop and find new markets. The reasons that neighbouring actors are even more important are several.

- They are heavily interested in formulating and keeping peace and stability in the region, as, if that is not the case, they are immediately affected by it.

- They stand to benefit from a successful outcome between these three countries. These benefits can be either that the neighbouring country will become an energy hub (e.g. Turkey), an end-user (e.g. India) or a seller of its own energy products, benefitting from the additional energy pathways that will open through this manner (e.g. Gulf States).

It is of great importance, thus, to explore the potential involvement of such state actors, contemplating both their capacity as political brokers, but also as financial supporters of the three countries:

- Turkey. Turkey is among the best positioned stakeholders on the stakeholder map. Its trade volumes with all three countries have been eyeing a surge. Trade with Iraq fell to $4 billion in 2016, but ever since it has skyrocketed to unprecedented figures, reaching over $15 billion in 2023. Similarly, trade with Turkmenistan had reached an all-time low of $500 million in 2018, and ever since it picked up steam and reached an all-time high of $2,06 billion in 2022. Finally, trade with Iran had fallen considerably because of the sanctions, from $21 billion in 2009 to $5 billion in 2019, however it is now again presenting an upward trend.

Considering energy flows, Iran is Turkey’s second largest natural gas supplier, after Russia, with Turkmenistan and Iraq being out of the picture at the moment. Conversely, Iraq has been Turkey’s top crude oil provider, with an annual amount of more than 13 million tonnes. Turkmenistan currently ranks much lower, with 0,7 million tonnes per year.

The figures show a growing trend of Ankara to grow closer with Baghdad, Tehran and Ashgabat and this can also be verified by its intention for investments worth in total $25 billion in Iraq, its intention to bring Turkmen gas to Europe and its support for the Saudi-Iran deal. This also shows the diplomatic capacity that Turkey possesses, as well as the political willingness to take initiatives and present itself as the mediator and the promoter of energy projects in the Middle East and Central Asia.

There are, however, challenges that exist. These have to do with the fact that Turkey, despite its rapid growth over the past decade, still is not considered as the powerhouse that could facilitate and provide investments for energy mega-projects.

Moreover, the rivalry of the Turkish government against the Kurdish population that is long-lasting and has far-reaching ramifications in its relations both with Iraq and with Syria, has not been resolved yet and there are no clear signs that it will be resolved in the near future. Finally, Ankara’s interests are limited only to the extent that the natural gas flows will transit through Turkey. A solution that would utilize Iranian ports for LNG exports would find opposition and result in a disengaged Turkey. - Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia is another perfectly positioned partner to support such an energy venture in the aforementioned countries. Its bilateral trade with Iran is a great example of that, as their trade flows were $1 billion before cutting bilateral ties in 2016.

In the beginning of 2023, the countries agreed to resume these very ties and this was immediately welcomed with a $14 million investment in Iran from Saudi investors to support the steel industry.

Correspondingly, Saudi Arabia trade with Iraq saw an exponential growth after 2016, reaching over $1 billion this year, whilst the only country that has not yet picked up on working more closely with Saudi Arabia has been Turkmenistan. Nonetheless, even in the case of Ashgabat, there have been joint consultations with Riyadh, with the ultimate objective of receiving investment in the energy sector, either on oil and gas or on renewable energy technologies and their deployment.

The strong point of Riyadh with regards to other regional actors is its vast financial resources that stem from its sovereign wealth fund, which has been developed through the profits it has gathered by its hydrocarbon’s economy, which just in 2021 presented an AUM of 1.98 trillion riyals. Another strong point is its flexibility, as it can facilitate both an LNG alternative, having access to ports like Jeddah, but also a pipeline infrastructure scenario.

However, weak points include the fact that its sovereign wealth fund has very limited focus on foreign investment, but also the fact that its relations with Iran are rather fragile and Riyadh has not positioned itself as a mediating power within the Middle East yet. - India. India is the most remote out of the three strong regional actors, however its presence in all three countries is also increasing rapidly. India’s trade with Saudi Arabia has seen a surge, from $30 billion in 2021 to over $52 billion for 2023, while over the next two years this figure is projected to double.

Similar increases are observed in the trade with Iran, Iraq and Turkmenistan, although the figures are much lower, being in the neighborhood of $2 billion in 2023. Despite being the largest of the three economies, India is providing only $7.28 billion as foreign investment and the lack of foreign aid support has been reflected also in the fact that both the TAPI pipeline, as well as the India-Myanmar-Bangladesh pipeline have not materialized as of now.

Moreover, India is a demand-hungry economy, so any solution that will not bring natural gas to the country will be disregarded. Finally, even a solution of LNG imports might face backlash from its immediate neighbours, Afghanistan and Pakistan, who are relying on the TAPI pipeline, which might bring social unrest in already destabilized countries

The Way Forward

Reflecting on the aforementioned analysis, it becomes clear that a trilateral partnership between Iran, Iraq and Turkmenistan to bring vast resources of energy into new markets during a time of energy crisis should become an issue of the immediate neighbourhood. Ankara’s diplomatic capacity was capitalised during the Russian invasion of Ukraine as it functioned multiple times as a mediator and this can be used to facilitate the trilateral dialogue and create stability in the region.

The only additional downside is the unresolved issue with the Kurdish population. This can be either resolved by Turkey itself, or Turkmenistan can provide a platform for dialogue, as the Iraq Turkmen population has worked on a mediating level between Arabs and Kurds several times. This, again, is expected to be a different case with only a few similarities with the foregoing one, however it can help set a foundation for dialogue and then adapt it according to the circumstances.

Regarding investments, Saudi Arabia and its sovereign fund can function as a good start, providing part of the wealth fund towards foreign investment in the region. However, it should not be the sole source of financing. Both India as well as other Gulf States can tend to this investment, giving a portion of their own sovereign wealth funds, such as Qatar and the UAE, followed by smaller ones such as Bahrain, Kuwait and Oman. T

The infrastructure can be a combination, facilitating both pipeline infrastructure (with examples such as the Friendship Pipeline) but also LNG infrastructure, resulting in an opening of multiple markets and ensuring that no state actor stays dissatisfied, which can lead to instability. Profits coming from these sets of projects can be diverted to the natural gas exploitation in Iraq, giving a new set of revenue streams and financial resources to modernize its energy infrastructure, which has become an issue over the past years.

Conclusion

As a conclusion, the Iran-Iraq-Turkmenistan triangle has been endowed with resources that have the potential to remove part of the energy insecurity issues that have been created because of the energy crisis of 2022, especially for markets such as the EU.

However, up to this date, most routes to provide these energy resources have been blocked predominantly due to political and financial reasons. In order for them to be overcome, a sophisticated and adaptive set of policies and strategies ought to be developed, both at a national and international level, from all the parties that are expected to participate.

The challenges are many, and with the current state of affairs in the Middle East it looks unlikely that a solution might be on sight, however, with the right combination of involvement from external partners, several relevant projects are expected to be unlocked, which can lead to economic growth that, in turn, can create a positive reinforcing loop of stability and growth.

This scenario has a small likelihood, with the most likely outcome to be continuing instability, nonetheless this analysis can serve as a roadmap to revert from such a vicious cycle.

Disclaimer. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of SpecialEurasia.

For those with an interest in acquiring comprehensive insights into the economic and political dynamics of the Middle East and Central Asia, we encourage you to reach out to our team by sending an email to info@specialeurasia.com. We are poised to facilitate an assessment of the opportunity for you to obtain a meticulously crafted and specialised report tailored to your intelligence needs.