Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 23 Issue 6

Author: Luca Urciuolo

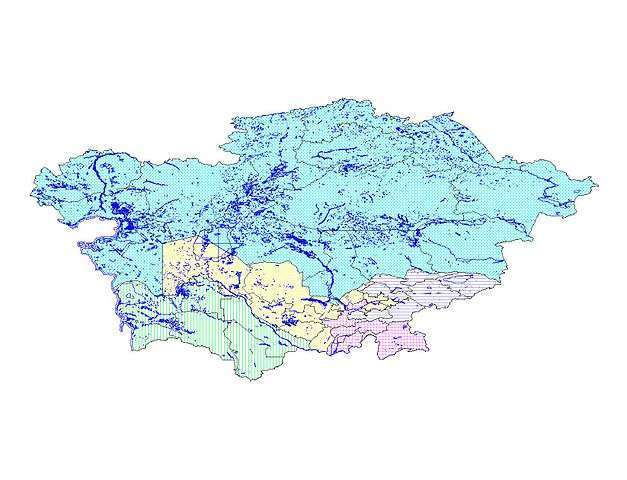

Due to the borders drawn by the former Soviet Union with no regard for ethnic, political, economic, and cultural factors, the Central Asian countries Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have faced each other for 31 years, and the recent military escalation highlighted regional instability and geopolitical strategies promoted by Dushanbe and Bishkek.

The recent outbreak of hostilities on the Kyrgyz-Tajik border represents a dangerous escalation from previous tension and skirmishes to a distinct act of aggression. In fact, what occurred in September 2022 appears more like an interstate conflict following a military incursion involving heavy weapons and in which civilian property and infrastructure appear to have been deliberately targeted. Besides the 984-kilometre-long border, of which only 504 km are demarcated, Kyrgyzstan hosts two Tajik exclaves, Vorukh and Kayragach.

Both sides have disputed ownership over various territories since independence in 1991, using different Soviet maps and agreements as the basis for their claims. Conflicts arise at specific points – clashes occur in the Ak-Sai, Kok-Taş, Samarkandyk, Tajik Corku, and Surh regions of the Kyrgyz villages. Kyrgyz presidents and Emomalī Rahmon — who has been Tajik president since 1994 — have been unable to settle this issue.

Moreover, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan tried to overcome the economic, political, and social problems that arose with the disintegration of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). These internal problems affect the relations between neighbours. While Tajiki and Kyrgyz authorities continue to find a solution to the border dispute, the situation in the border regions of both countries is in a deadlock. Tensions often arise between border guards and citizens due to the density of fertile farmland, murky territory, illegal crossings, animal grazing, and control of water resources. This is also since Kyrgyz and Tajik communities had common property rights to access and use natural resources under the system of land tenure based on property rights backed up by Soviet state authorities.

Border skirmishes or escalation?

Conflicts have intensified across the former Soviet Union. On September 14-17, 2022, armed clashes occurred on the Batken region’s border in southern Kyrgyzstan between the Tajik and Kyrgyz military forces. This was a dramatic escalation of tensions between the two countries in a region where periodic provocations and skirmishes have become part of everyday life. Both countries blamed each other for starting the conflict. As of September 28th, according to official data from Kyrgyzstan, 63 Kyrgyz were killed, and 195 people were injured.[1]

Furthermore, according to the press service of the Ministry of Emergency Situations of Kyrgyzstan, 136,770 people were evacuated to safe areas.[2] On the other hand, the Tajik authorities reported the death of 74 people during the armed conflict on the border with Kyrgyzstan.[3] Much of the conflict centres around Vorukh, a Tajik exclave surrounded by Kyrgyz territory, along a mountainous border that remains largely not demarcated.

Although the Kyrgyz-Tajik border is the location of regular clashes of various scales and gravity, in this case, it appears to be an act of aggression by Tajikistan against Kyrgyzstan. Judging by the sheer scale of the operation, the amount of heavy military machinery, and the number of army troops, it appeared as a deliberate and planned Tajik military operation. One feature that sets this incident apart from previous border skirmishes is that Tajikistan targeted civilian infrastructure in undisputed Kyrgyzstan’s territory, away from the Kyrgyz-Tajik border. Batken, the regional capital sitting 10 km from the border and indisputably Kyrgyz territory, was reportedly shelled. Indiscriminate shelling indicates a possible goal of driving civilians out of the area.[4]

The situation finally escalated when a forceful Kyrgyz response echoed Tajikistan’s military actions. Rahmon and his Kyrgyz counterpart, Sadyr Japarov, spent several days next to each other at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit in Samarkand. Both presidents expressed commitment to resolving any problems through diplomatic means.[5] Moreover, it seems they missed a critical opportunity to de-escalate the situation early on, building on a legacy of lax leadership on both sides when settling the not demarcated sections of the Kyrgyz-Tajik border.

The escalation was preceded by populist moves by the Kyrgyz government regarding border regulation and the resolution of territorial disputes. Territorial sovereignty and border security were part of Japarov’s and his ally, head of the State Committee for National Security, Kamchybek Tashiev’s electoral campaigns in late 2020. Upon being elected in early 2021, the government purchased a few Turkish Bayraktar drones and Russian “Tigers” — armoured personnel carriers — which replaced old Russian UAZ, off-road vehicles that were easily penetrable by bullets. The government decided to display its new purchases by throwing a military parade in the capital in August 2021, with some of the equipment then transferred to the border area.[6]

Government officials also boasted that they would resolve border disputes with Tajikistan soon, perhaps relying on their successful negotiation of border issues with Uzbekistan.[7] On the Tajik side, the regime has been militarising the border for a long time. In recent years, Tajikistan has received military training and aid on a large scale, including from Chinese, Russian, Iranian, and American forces concerning Afghanistan. The latest effort in this direction is opening a facility to produce Iranian-designed Ababil-2 tactical drones.[8] This escalation suggests that using the language of “border clash” or “border skirmish” to describe what happened, as various media outlets and commentators have done, obscures more than illuminates it.

Old issues and the shadow of third parties behind the conflict

While it might still be early to dive into analytical conclusions, there is a range of potential reasons why Tajikistan engaged in an armed attack on Kyrgyzstan at this moment. In the last ten years, more than 150 tensions and conflicts were recorded between the two countries concerning resource access and use clashes between Kyrgyz and Tajik border communities.[9]

Especially since the violent outbreak in April 2021, the region’s border has been tense. The disputes are causing multiple conflicts over the access and use of natural resources such as water for irrigation purposes and pasture grounds for grazing animals. Pasture resources are getting scarcer every year due to population increases among both border communities and limited productivity caused by climatic conditions of the rangelands. However, livestock production is a fundamental component of the economies of both countries, and mountain pastures remain an essential natural resource as they are the primary and cheapest source of forage in both countries. Since many invest in livestock, the number of livestock is also growing.

Consequently, there is an increasing demand for pasture use every year. The conflicts on pasture resources in the border areas mainly arise when Tajik herders let their livestock graze on pastures belonging to Kyrgyz territory. Since there are no pastures on the territory of Tajikistan in the border region available, Tajik rural communities directly depend on Kyrgyz pasture resources. Since the pastures are not enough for Kyrgyz pasture users and referring to the current Kyrgyz Pasture Law that prohibits foreign herders the grazing on Kyrgyz pastures, the Kyrgyz Pasture Committees chase Tajik herders grazing on the pastures in Kyrgyz territory away whenever they see them.

However, Tajik pastoral communities do not think of themselves as foreigners on these pastures since these resources were used by their ancestors during the times of the Soviet Union. In addition, Tajik pastoral communities believe that parts of these border grazing areas belong to Tajikistan. This assumption is understandable because Kyrgyz and Tajik border communities lack information on where the disputed areas are located.[10]

The use of water resources represents another incentive for the conflict. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan share about 40 channels. Some of these channels rise in Kyrgyzstan and flow to Tajikistan and vice versa. Many Kyrgyz farmers complain that Tajiks living upstream of the river use too much water and less remains for Kyrgyz farmers living downstream. In turn, downstream Tajik communities complain about too little water arriving in their territories. This conflict arises every year during the irrigation period from April to June.

The current decaying water infrastructure on the Kyrgyz-Tajik border exacerbates the situation. This is because some of the hydraulic facilities are in a transboundary area which lacks both the Tajik and Kyrgyz state’s attention. Neither of these countries wants to invest in reparations since there is no unique organization, agreement, or law on that issue. As a result, much water is unavailable for agricultural use.

There are also purely political reasons for analysing the causes of the conflict in a period of enormous tension and instability in the post-Soviet area. There is speculation that Tajik President Rahmon plans to hand over his position to his son Rustam Emomalī, currently the speaker of Tajikistan’s Parliament.[11] Such a succession process usually requires a demonstration of power – a short victorious war showcasing regime stability. In addition, Rahmon might wish to distract the attention of both domestic and international audiences away from the fate of the resilient and defiant protests in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region (GBAO) populated by the Pamiri minority.

The military conflict started on the same date when the governments of China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan signed in Samarkand a long-anticipated agreement to construct a railroad linking these countries that would establish a shorter route to Europe, bypassing sanctions-hit Russia.[12] Thus, according to some Kyrgyz officials, the clashes on the Tajik and Kyrgyz borders would result as a warning about the discontent of Russia, which throughout the history of the Central Asian countries has tried to make the region as economically dependent as possible. Therefore, with Putin’s support, Tajik forces would invade the territory of Kyrgyzstan.

Furthermore, many feared that Kyrgyzstan’s neutral position regarding the war on Ukraine would cause discontent in Moscow and perhaps lead to Russia’s siding with Tajikistan. According to this perspective, the two countries are in this battle because of Russian tactics. There is also who, like the Deputy of the State Duma of the Russian Federation Alexey Chepa, supposes that external forces, primarily enemies of Russia, have decided to take advantage of the situation and create conflicts in the region by using the internal problems of Tajikistan and the conflict situation with Afghanistan. All this chaos is aimed at using conflicts to discredit Russia further.[13]

Conclusion

Although Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan reached an agreement to demilitarise a conflict-afflicted section of their shared border on September 25th, the dispute is far from over. The whole of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) is shaking, with wars between Russia and Ukraine, Armenia and Azerbaijan, and now between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The states of the former Soviet Union are all observing an ongoing shattering of the existing order with uncertainty and fear. What is next? The Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) offered diplomatic mediation, but there was no positive response from the parties.

Moreover, the CSTO has not previously developed a mechanism to solve similar problems. It is known that after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of border conflicts in some countries, peacekeepers were sent to the border regions under the CIS for peacekeeping purposes. However, such a system does not solve the root of the problem.

For this reason, each country tries to defend its borders or the lands it claims with external support or its own means. While Tajikistan enjoys significant support from Russia and, more recently, from Iran, it seems that Kyrgyzstan is seeking a similar way to balance the power of its neighbour. Many experts see the solution to the conflict between the two states in border demarcation. Yet, this process can be complicated when considering natural resources and the location of houses in a chessboard form of border communities. Therefore, to manage the current situation, interventions by both countries’ governments are needed to strengthen cooperation, increase capacity building in resource management, promote effective inter-ministerial coordination and improve independent monitoring systems, as well as a more substantial involvement of local users and stakeholders. Lastly, these two countries need an intergovernmental agreement to define property rights to access and use water and pasture resources.

Sources

[1] Novosti.kg (2022) Число погибших кыргызстанцев в ходе вооруженной агрессии Таджикистана увеличилось до 63. Новости.кг. Link: https://novosti.kg/2022/09/chislo-pogibshih-kyrgyzstantsev-v-hode-vooruzhennoj-agressii-tadzhikistana-uvelichilos-do-63/

[2] AKIpress News Agency (2022) More than 58,000 Batken residents return to their homes – Ministry of Emergency Situations. Link: https://akipress.com/news:680570:More_than_58,000_Batken_residents_return_to_their_homes_-_Ministry_of_Emergency_Situations/

[3] Radio Ozodi (2022) Имена 74 жертв конфликта 14-17 сентября на таджикско-кыргызской границе. Link: https://rus.ozodi.org/a/32042707.html

[4] Aijan Sharshenova (2022) More than a ‘Border Skirmish’ Between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/more-than-a-border-skirmish-between-kyrgyzstan-and-tajikistan/

[5] Prezident Kyrgyzskoj Respubliki (2022) Президент Садыр Жапаров провел переговоры с Президентом Таджикистана Эмомали Рахмоном по ситуации на кыргызско — таджикском участке госграницы. Link: https://www.president.kg/ru/sobytiya/novosti/23347_prezident_sadir_ghaparov_provel_peregovori_sprezidentom_tadghikistanaemomalirahmonom_posituacii_nakirgizsko_tadghikskom_uchastke_gosgranici; Ministerstvo Inostrannyh del Respubliki Tadzhikistan(2022) Встреча с Президентом Кыргызской Республики Садыром Жапаровым. Link: https://mfa.tj/ru/main/view/11021/vstrecha-s-prezidentom-kyrgyzskoi-respubliki-sadyrom-zhaparovym

[6] Борубек Кудаяров (2021) Как выглядит военная техника, которую завтра покажут на параде. Фото. Kaktus.media. https://kaktus.media/doc/445166_kak_vygliadit_voennaia_tehnika_kotoryu_zavtra_pokajyt_na_parade._foto.html

[7] Catherine Putz (2021) Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Border: ‘Resolved 100 Percent.’ The Diplomat. Link: https://thediplomat.com/2021/03/kyrgyzstan-uzbekistan-border-resolved-100-percent/

[8] Press TV (2022) Tajikistan launches production of Iran’s Ababi 2 tactical drone. Link: https://www.presstv.ir/Detail/2022/05/17/682255/Iran-inaugurates-production-site-for-homegrown-Ababil-2-tactical-drone-in-Tajikistan

[9] Nazir Aliyev (2022) Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan border disputes continue for 31 years. Anadolu Agency. Link: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/kyrgyzstan-tajikistan-border-disputes-continue-for-31-years/2687807

[10] Gulzana Kurmanalieva (2018) Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan: Endless Border Conflicts. L’Europe en formation. Vol. 1, n. 385, 121-130 pp.

[11] Kamila Ibragimova (2022) Tajikistan: President’s son adopts growing role on center stage. Eurasianet. Link: https://eurasianet.org/tajikistan-presidents-son-adopts-growing-role-on-center-stage

[12] Joanna Lillis (2022) China, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan sign landmark railroad deal. Eurasianet. Link: https://eurasianet.org/china-kyrgyzstan-uzbekistan-sign-landmark-railroad-deal

[13] Aisulu Duishalieva (2022), Kyrgyz-Tajik Conflict: Small States Becoming Victim in Games of The Great Powers. Modern Diplomacy. Link: https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2022/09/21/kyrgyz-tajik-conflict-small-states-becoming-victim-in-games-of-the-great-powers/

Disclaimer. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of SpecialEurasia.