Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 23 Issue 1

Author: Silvia Boltuc

Over the years, the Islamic Republic of Iran has consolidated its relations with the countries of Central Asia, exploiting either the Persian common ethnic-cultural element or proposing itself as a logistic hub for the energy sector and trade corridors.

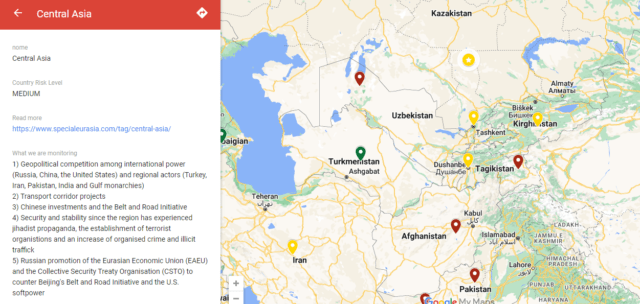

Theatre of clashes between the great powers in recent centuries and the epicentre of the “Great Game” previously between the British and the Tsarist empires, then between the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War, and nowadays between Russia, the United States and China, Central Asia has attracted the interests of a key Eurasian regional player such as the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Iran cannot exert the same pressure in the economic, political and military fields as Russia or China. Nevertheless, Tehran has always tried to create its sphere of influence in the region by exploiting commercial and/or historical-cultural aspects. Indeed, the Islamic Republic of Iran, thanks to significant religious and ethnic affinities with several areas of the region (especially in Tajikistan), as well as offering access to essential seaports and participating in security issues related to Afghanistan, was able to achieve a significant increase of ties with Central Asia. In this regard, Tehran has sought to strengthen bilateral relations with Central Asian governments.

Against the backdrop of tense relations with the Arab world and the friction with the West generated by the Islamic Revolution, relations with Asia represented compensation for Iran’s isolation costs. In the early 1990s, taking advantage of common ethnic and linguistic aspects due to the historical heritage (a significant part of Central Asia for a long time was under the sphere of influence of the Achaemenid and Sassanid empires), Tehran initiated an active policy in the region, starting from Tajikistan. Subsequently, the penetration strategy expanded to the other Central Asian states.

For central Asian republics, Iran offers many valuable assets such as corridors and energy transport infrastructures. Furthermore, Tehran might supply technology and establish trade exchanges. Most notably, the Islamic Republic of Iran exerts its influence on important regional organisations: the Organization for Economic Cooperation (ECO), the Organization for Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Tehran is also an observer country of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which includes Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

It should be emphasised that unlike the Middle East, where Tehran’s policy of growing influence was perceived as a claim to exercise a decisive political-military role, in Central Asia, the Islamic Republic has traditionally acted in a more balanced way with the result of becoming an excellent commercial partner. As a demonstration of Iran’s more pragmatic approach, the relations with central Asian republics have been less affected by changes in the leadership of local governments compared to Middle Eastern countries. Even during the civil war in Tajikistan, Iran, in solidarity with the Islamic opposition, opted for a political solution based on the division of power.

As for infrastructures, already in the first decade of the century, Iran had carried out substantial works in collaboration with the countries of Central Asia: a concrete example is the Tejen-Serakhs-Mashhad transit corridor which provided the Central Asian republics with ‘access to ports in the Persian Gulf, to markets in the Middle East, in South and Southeast Asia, and has also become an essential source of foreign exchange earnings for Turkmenistan.[1] Over the years, Iran cooperated with central Asian countries to construct hydroelectric power plants. Moreover, Teheran planned to make Iranian electricity networks work in parallel with the local ones and to build gas pipelines and other common infrastructures. Not less important is the role played by Iranian ports in the Gulf, particularly the port of Chabahar, the first Iranian port in deep waters and a direct competitor of the Pakistani port of Gwadar.[2] The ports of Iran provide access to international waters and ensure the passage of Indian goods to the markets of Central Asia.

Finally, it is possible to affirm that the good relations between Iran and the two countries strongly present in the area, China and Russia, have allowed the Central Asian republics to relate to one or the other without significant conflicts of interest, being able to diversify its portfolio of business partners. Together with these critical regional actors, Tehran attempted to stabilise the area by playing an essential role in the fight against terrorism affecting Central Asia’s countries.[3]

The Iranian-Tajik relations

On May 30th, 2022, took place a historic meeting between the Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi and the Tajik president Emomali Rahmon, followed by the signing of 16 cooperation agreements. This event gave a new impetus to relations between the two countries which had faced a crisis and a cooling in recent years.[4]

As Tajik President Emomali Rahmon said, Tajikistan has expressed interest in accessing Iran’s seaports and using the ports of Chabahar and Bandar Abbas to transport goods and products. Iran and Tajikistan also discussed the construction of the Istiklol tunnel and the Sangtuda-2 hydroelectric power plant on Tajik territory.

This renewed interest between the parties followed a period of crisis between Dushanbe and Tehran. In 2015, in fact, the leader of Hizb Nahzati Islomii Tojikiston (Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan), Muhiddin Kabiri, went on an official visit to Tehran and met with the supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, raising the grievances of the Tajik authorities who had interpreted this event as Iranian support for the opposition.[5]

In response, Tehran denied the charge and demanded the return of the properties of the arrested Iranian billionaire Babak Zanjani, owner of assets in Tajikistan. As a result, the Iranian authorities filed a lawsuit against Babak Zanjani for embezzlement of billions of dollars from the Ministry of Petroleum. The investigation revealed that Zanjani held 2.4 billion dollars in the National Bank of Tajikistan. Dushanbe categorically denied any involvement.

The disagreement between Dushanbe and Tehran contributed to Tajikistan’s strategy of closer relations with Saudi Arabia.[6] Riyadh allocated 200 million dollars in 2017 to build the parliament and government buildings. However, this didn’t stop Dushanbe and Tehran from establishing cooperation two years later.

In June 2019, there was a thaw in relations between Iran and Tajikistan. On June 1, 2019, Tajik Foreign Minister Sirojiddin Muhriddin met with his Iranian counterpart Javad Zarif and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani in Tehran. Subsequently, Iran decided to continue funding several projects in Tajikistan, particularly the construction of the Istiklol tunnel.[7]

The recent rapprochement between the parties follows Tehran’s cultural and commercial diplomacy project: in fact, the Islamic Republic of Iran and Tajikistan share a common Persian language and culture, elements the Iranian government has often exploited to maintain its position and its influential role in the region.[8] Iran, therefore, is trying to realise its ambitions in the so-called ‘Persian area’, where Tajikistan plays a key role. Furthermore, Dushanbe represents a ‘window’ on Central Asia and neighbouring Afghanistan, where lives a Tajik minority and a significant Shiite community, the Hazara.

Iranian relations with the Turkic countries of Central Asia

Compared to Tajikistan, where the Islamic Republic of Iran can exploit the common linguistic and cultural identity, the bilateral relations with the other Central Asian republics, where the Turkic element is predominant, are different. Even in this case, however, Tehran has been able to forge strong ties with some of the areas where the Persian cultural and linguistic heritage is still present, for example, in the Uzbek cities of Samarkand and Bukhara.

Kazakhstan is linked to Iran through states’ joint participation in resolving international conflicts. In addition, Kazakhstan has repeatedly hosted negotiations on the Iranian nuclear program. Trade turnover between the two countries has increased significantly since the opening of the Eastern Caspian railway line in 2014, thanks to which goods are delivered faster and cheaper (in the future, passengers may also travel along the route).[9]

Despite Uzbekistan’s recent reluctance to develop relations with Iran, the bilateral partnership is rising. Potential transit corridors are under discussion as trade between Uzbekistan and Iran grows, mainly in the agricultural sector. Both states participated in the Afghan peace process, which is essential for Iran to strengthen its role in guaranteeing regional stability.

Kyrgyzstan is the only country in the region that successfully signed a ten-year cooperation agreement with Iran in 2016 and was the first to acquire docks in the port of Chabahar in the Gulf of Oman in 2007. Access to the sea is essential for landlocked Central Asian states seeking to enter trade routes. India helped Turkmenistan secure access to the port of Chabahar, reaching regional markets through the Central Asian republic.

Conclusion

Iran should continue to interact with the Central Asian states on a bilateral basis, identifying the most advantageous areas for a balanced rapprochement of all parties. Tehran should also promote its economic vision through cooperation in regional economic and energy integration projects.

The country, in fact, has relaunched itself as a primary Eurasian energy hub, connecting, among others, its electricity grids with those of many regional entities. In addition, the Islamic Republic of Iran has entered the main regional economic corridors: the International North-South Transit Corridor (INSTC) and the New Silk Road (BRI). In this context, Iranian ports have an essential role.

Tehran has invested in the strategic role of its seaports and signed agreements with crucial international port hubs such as those of Oman, becoming not only the gateway that allows Indian goods to reach Central Asian destination markets by avoiding Pakistan but also providing an alternative route to destabilised Afghanistan for actors interested in regional trade.

Finally, it is essential to underline that Iran has already received preliminary approval to become a full member of the Shanghai Russian-Chinese Cooperation Organization (SCO), and the Eurasian Economic Union has concluded a preferential trade agreement with the country. This agreement, together with the several free economic zones established in Iran, facilitates investment in the country.[10]

Sources

[1] Turkmenistan Railway Assessment (ND) Logcluster. Link: https://dlca.logcluster.org/plugins/viewsource/viewpagesrc.action?pageId=853040.

[2] Silvia Boltuc (2021) Geopolitica del porto iraniano di Chabahar, Geopolitical Report ISSN 2532-845X Volume 5, ASRIE Analytica. Link: https://www.specialeurasia.com/2021/07/14/geopolitica-iran-chabahar/.

[3] Francisco Olmos (2022) Busy Times in Iran-Central Asia Relations, The Diplomat. Link: https://thediplomat.com/2022/06/busy-times-in-iran-central-asia-relations/.

[4] Prezidenti Chumhurii Tochkiston (2022) Маросими имзои санадҳои нави ҳамкорӣ миёни Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон ва Ҷумҳурии Исломии Эрон (Signing ceremony of new cooperation documents between the Republic of Tajikistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran). Link: http://www.president.tj/node/28397.

[5] Tajikistan concerned over Iran’s decision to invite leader of banned IRP to conference (2015) ASIA – Plus. Link: https://www.asiaplustj.info/en/news/tajikistan/politics/20151230/tajikistan-concerned-over-iran-s-decision-invite-leader-banned-irp-conference.

[6] Hamidreza Hazizi (2017) Saudi Arabia woos Persian-speaking Sunnis in Central Asia, Al-Monitor. Link: https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2017/08/iran-tajikistan-saudi-arabia-influence-tension-central-asia.html.

[7] Tajik foreign minister meets with Iranian president in Tehran to discuss trade and economic cooperation (2019) ASIA-Plus. Link: https://asiaplustj.info/en/news/tajikistan/politics/20190603/tajik-foreign-minister-meets-with-iranian-president-in-tehran-to-discuss-trade-and-economic-cooperation.

[8] Giuliano Bifolchi (2022) Iran and Tajikistan expanded their cooperation in different fields, Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 20 Issue 1, SpecialEurasia. Link: https://www.specialeurasia.com/it/2022/06/01/iran-tajikistan-cooperation/.

[9] Keith Barrow (2014) Iran – Turkmenistan – Kazakhstan rail link completed, International Railway Journal. Link: https://www.railjournal.com/regions/asia/iran-turkmenistan-kazakhstan-rail-link-completed/.

[10] Silvia Boltuc (2021) Iran interests in Eurasian Economic Union: possibilities and constraints, Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 9 Issue 2, SpecialEurasia. Link: https://www.specialeurasia.com/2021/07/09/iran-eurasian-economic-union/.

Analysis in media partnership with Opinio Juris. It is possible to read the Italian version of this analysis at the following link: Sulla Via di Samarcanda