Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 16 Issue 5

Author: Amedeo Gasparini

Today’s European Union is characterised by many crises entwining one another, resulting in politicisation and polarisation around issues and challenges of the EU itself. At the same time, the concept of the EU has progressively become an object of politicisation and polarisation. Victim of a vast political blame-shifting process, the EU is depicted by populist parties as the source of all evils afflicting the European societies.

The Eurocrisis witnessed a boost in the politicisation of Europe[1] and has been fostered by the Global Financial Crisis’ legacies, uncontrolled immigration,[2] pan-European identity problems, and North-South divide.[3] These elements offer the picture of a weak EU, unable to tackle right- and left-wing populistic claims and accusations, which – in turn – try to destabilise it. Hostile foreign and internal attacks and weaknesses within the EU itself inevitably led the European project to a “polycrisis”.[4] Populist parties not only weaken the concept of Europe in many voters’ minds but also contribute to offering a distorted and simplistic image of the EU, regardless of the positive outcomes this latter has achieved in the last decades. The European “polycrisis” risks erasing the legitimacy of many praiseworthy goals the EU has been able to accomplish. The EU is sick and in the last ten-twelve years has experienced challenges in many fields: political, financial, economic, social, and sanitary crises simultaneously occurred in the “Old Continent”.

Europe, as a philosophic concept, and the EU, as a political architecture, are facing much structural crisis, a set of troubles in today’s globalised world that weakening the European identity, the perceived legitimacy of the EU as a (geo)political actor and the perception of the EU itself by many European citizens, who accuse Brussels of democratic deficit.[5] Citizens experienced GFC’s toughness, the uncontrolled influx of migrants and refugees,[6] and a period of distress fracturing the EU’s cohesion widening the centre-periphery gap.[7] Particularly, the “immigration issue” has become crucial in the economic recession. Foreigners are accused of taking jobs away from local workers,[8] and this further fuelled the populist parties’ consensus. The rise of defensive nationalism[9] did not help the process towards further inclusive integration in a broader and stronger European common home. The rise of inequalities has been a further element of crisis. Nonetheless, all the post-Brexit saga did not help the idealistic legitimacy of the EU – perceived just as an authoritative body imposing obligations – exposing it to further criticisms. Another important factor that corroborates the idea of a fragile EU affected by “polycrisis” is the North-South cleavage. Eurocrisis is different from (European) “polycrisis”, but the two concepts can go together. The North-South divide is an issue that weakened the EU.

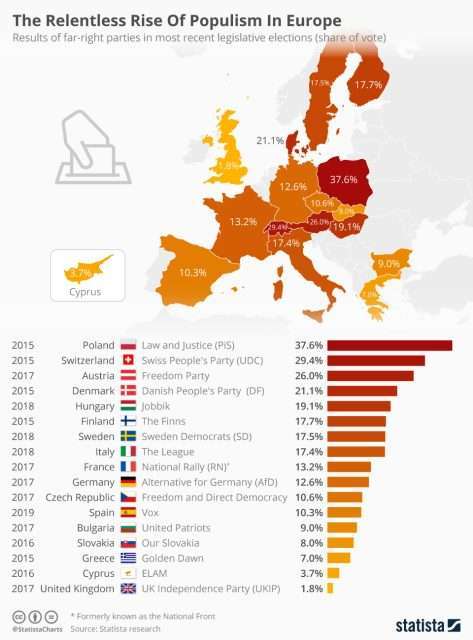

The conflicts between debtor and creditor countries contributed to enhancing Europe’s politicisation.[10] Northern and Southern Europe blame one another for the mismanagement of the EU. On the one hand, the Northern countries are not willing to tolerate economic and fiscal indiscipline as well as non-compliance with the treaties’ common rules. On the other hand, Southern countries blame the North for being hegemonic and dominant, as well as too severe on economic-budgetary issues. The above-mentioned crises exposed the EU to a wide politicisation by populist parties. Not only these have been thriving in every Member State, but were also able to build a solid political consensus by blaming the EU for everything bad that happened to “the people”. Though there are differences between European realities and populist parties in Europe, in the populist narrative there is no distinction between EU and Europe. Populist parties politicise and exaggerate current objective challenges, problems, flaws, and shortcomings of the European institutions, policymaking, and EU in general, simplifying important and relevant matters for gaining political consensus, increasing the polarisation in the EU over different policy and political issues. How then populists politicise the concept(ion) of the EU and increase hostility towards it to gain electoral consensus? How populist movements politically constructed a negative myth of the EU, drawing it as a scapegoat and source of all evils?

Populism and blame-shifting mechanism

Populism, a contested concept, is a “narrow-minded, anti-universalist, nationalistic, anti-foreigner, anti-democratic, reactionary” [11] political method, and way of conducting politics. This definition is not exhaustive, also because there are many populisms, but I shall focus on populism in the European sphere, where demagogue-populist movements identify common targets and scapegoat terms of targets show common elements. Regarding EU’s current affairs and management, populist rhetoric is used and adopted by both the (extreme) right and (extreme) left of the political spectrum. Despite the differences of the populist movements, one main link between them is their hostility vis-à-vis Brussels. Furthermore, they all agree that their State is no longer the sole site of authority.[12] In the populist perspective, the EU is guilty of having stolen single Member States’ identity, as well as the decision-making power over many fields and having forgotten their citizens. In this regard, it is easy to explain the Manichean worldview populists parties propose. On the one hand “the people”, on the other “the élites”. The lack of transparency and accountability is the top critical point of the populists’ concerns attacking the EU.[13] The most efficient strategy European populist movements use while demolishing, discrediting, and undermining the concept of Europe and EU, is the blame-shifting mechanism.

This latter consists in shifting the domestic problems to the European level, making the EU or Europe itself (both used interchangeably) as the main problem of local-national failures. The blame-shifting method is based on the populist concept of Euroscepticismm[14] which consists in the blind distrust of the EU and the willingness to create a new international European order based on single sovereign nations.[15] The EU has become the target of populist movements in Europe. Demagogic leaders complain about the EU’s lack of support and intervention in the domestic context. Simultaneously, populist leaders argue that “the people” have been forgotten by Brussels, which failed to protect them from the “polycrisis”. Shaping the EU as the origin of all evils is vital for populist movements: scapegoating is easy and allows demagogues to score easy political points. The EU’s internal weaknesses help to fuel the populistic-demagogic anti-EU sentiment. Populist leaders can transform the EU into a “great Satan” to fight through an ideological nationalistic crusade. And the attacks on Brussels are equally carried out from “pauperistic” movements (left-wing populism) and “sovereigntist” movements (right-wing populism). Blame-shifting aims and is states’ self-de-responsibility; and it also entails the fact that populists are not able (or, more probable, willing) to accept the EU’s successes in many fields.

Populist leaders’ dream is eventually the dismantling (disguised as “radical reform”) of the EU, after a long process of (further) politicisation of that issue, through the blame-shifting mechanism. Populist parties and leaders are delegitimising every European institution, particularly the European Commission, which takes all the blame for the unease with European integration,[16] the European Parliament, and the European Central Bank. The continuing politicising of the European institutions (meaning-making the EU guilty regardless of its concrete objectives) helps to extend the distance between the “common man” and the European institutions. Following the blame-shifting method (finding guiltiness that reassures frightened and disillusioned electors), the EU is a “catch-all” problem. According to the populist parties, the EU is the perfect entity behind all the asperities that touched the single Member States and their domestic institutions. The GFC mixed with the Euro crisis was lethal for the pro-EU and pro-Europe supporters. Brussels has not always been able to coordinate efficient decisions. But the “polycrisis”, which was increased through the demagogic blame-shifting technique and polarised the opinions around the concept of EU, was only partially triggered by the GFC.

Populist movements should indeed thank the economic cataclysm, which allowed them to build a remarkable political consensus in any European country. Identifying “Europe” as both source and cause of the “polycrisis” affecting the Member States was successful for most of all (European) populist parties. The lack of common perceived identity and the detachment of Brussels from the “common people’s problems” were instrumentally used by populists to increase the “polycrisis” itself, amplifying the divide between “the people” and the EU. Euroscepticism goes hand in hand with political scapegoating of the EU and it corroborates the idea that power dispersion is a threat.[17] Many populist leaders argue that centralising political power at the European level is dangerous for the Member States. There are many studies around the countries’ inclination of being Eurosceptic, thus inclined to blame-shifting. “In the enlarged EU, strong Euroscepticism is […] represented in countries with more concentrated party systems”.[18] Populists are fervently against Brussels’ centralisation (accused of being too distant from “the people”), but if they want to promote total centralisation in their nations (where the power’s grasp would be easier and more likely for them), they should be ready to renounce to their favourite scapegoat, the EU.

Politicisation and polarisation

Populist leaders were able to adapt and present to their electorates a total politicisation[19] of the EU and Europe. Going beyond the objective benefits, outcomes, and results of (an imperfect and incomplete) Union, they present just the EU’s shortcomings, scapegoating it. The politicisation of the EU is a process of “visible contestation related to the various dimensions of European integration”.[20] Politicisation means moving something into public choice[21] and populist parties across Europe – always through the scapegoating/blame-shifting mechanism – were able to bring the concept of EU itself into the political arena. The EU has become the object of a virtual popular referendum; a dominant issue in the political field, a symbol of political cleavages. Europe, as well as the EU, has had a growing importance in the political debate, especially after the GFC, but it was not dominant as it is today; and surely a biased perception of it across the EU’s societies was not overwhelming. Left- and right-wing populist parties not only critically introduced the concept of the EU into the political debate but politicised the concept itself. This means going beyond the EU’s objective merits, offering a rough picture of it for one’s political benefits. The greatest damage of populist politicisation is that this latter leads to (further political) polarisation, which does not help the debate (around EU and not only) in any way.

The politicisation processes can “be provoked not only by a lack of legitimacy in decision-making by strong international institutions but also by a lack of effective institutions”.[22] The lack of institutions might make feel (part of) the electorate alone and abandoned, and thus prey of populist partial and biased versions of the EU’s architecture. Today’s EU appears weak and illegitimate to the eyes of many, seriously affected by political polarisation, which prevents people to see the EU’s true colours: advantages and disadvantages. Polarisation is the direct consequence of the continuing blame-shifting and politicisation of the EU in the current (and past) “polycrisis”. On the other hand, it is bizarre to see how the “EU is popular when the European economy is booming and is blamed when the economy is performing badly”.[23] This should bring many to the conclusion that populistic-demagogic parties exploit the concept of the EU for their political purposes. Politicisation might be seen as a natural political process that occurs when “issues become salient when actors polarise in their views of these issues, and when they can mobilise public opinion accordingly”.[24] However, politicisation should not degenerate into polarisation. There has been a “politicisation of European integration over the past two decades in terms of increasing salience”. Thanks to (and because of) the blame-shifting process, politicisation led to an enormous polarisation, as well as an aggravation of the European polycrisis.

Not surprisingly, this resulted in turn into more polarised political actors. Politicisation is not only something affecting the concept of Europe and EU but is a process that occurred in many institutions across the world. Polarisation deriving from the politicisation (deriving in turn from blame-shifting), is not only something applicable to the European case. And within facing the discredit that populist leaders and movements operated (and are operating) towards the EU, what are the traditional parties doing? How do they react to the populist wave/phenomenon, the politicisation, and the polarisation of the EU through the scapegoating/blame-shift mechanism? Many of them are perceived as weak by the electorate and “the people”. Most of all, the traditional parties are unwilling to defend an unbiased representation of the EU and Europe as a whole. They do not add convincing counter-arguments to the populist EU blame-shifting discourse and within their sometimes-clumsy defence of the EU are only making the situation worse, politicising, in turn, the concept of EU, thus increasing political polarisation. If criticising and scapegoating the EU does not help in any way to build a “better” and “fair” European house, on the other hand, sometimes is ridiculous the excessive, blind, and pompous “Europhylism” of some parties opposing populist movements. In other terms, by blindly emphasising the concept of EU and Europe, these parties indirectly help populists radicalise themselves, bringing, therefore, the “polycrisis” even further, stressing the politicisation and polarisation as well.

The traditional parties are fazed by populist movements. They are incapable to oppose the scapegoating process of the EU with relevant arguments, but since there is a huge polarisation over the EU (and in the EU) they are not able to give a credible response. “Mainstream parties which have typically been pro-European have traditionally sought to depoliticise European integration in domestic arenas in many ways”.[25] Secondly, “a party is more likely to politicise an issue if the other parties in the system emphasise the issue as well but adopt a markedly different position”. The European polycrisis has seen a boost in the politicisation of Europe and so not only a polarisation over the concept of EU by populists but also a partisan blame-shifting. The negative political construction of the EU – built up by populist parties via a process of scapegoating and blame-shifting – brought to a devastating political polarisation. Both within and over the EU. This politicisation of the concept of Europe and the EU has been noxious. Still today demagogic parties are challenging the old and traditional set of EU politics. “The diversity of politicisation puts additional stress on a consensus-based political system that is […] not well equipped to absorb and channel political conflicts”. I would suggest a formula to simplify the European “polycrisis”: “P2 2P”, which means that populism (P) brings to (2) two (2) other “p” (P), which are politicisation and polarisation of the EU.

The consequences of P2 2P

In the last years, there has been an increase in politicisation, deriving from an increasing polarisation (increasing by the constant scapegoating of the EU from populist parties) of the EU. Both politicisation and polarisation are bad for political institutions and democracy’s health because they drive the electorate’s attention into a distorted interpretation of serious political matters. Some argue that the politicisation resulting from the (European) “polycrisis” could eventually be good for the EU itself, which could see it as an opportunity for the European institutions.[26] Indeed, “politicisation could thus strengthen the resilience of the European political system regardless of whether outcomes”. “P2 2P”: Populism brings to politicisation, thus to polarisation, over and within the EU. Politicisation multiplies and feeds polarisation. Politicising facts has the only effect to make issues more controversial. The result is the radicalisation of the political debate. In many European political arenas, the debate is no longer on the merit of the issues, but simply arm-wrestling with the European institutions to increase one’s electoral consensus.

As for populist movements, the only source of legitimisation of most of their movements in Europe is based on the delegitimisation of the EU, but populism and their institutions’ discredit have long-lasting effects. Thus, it has political polarisation. When one creates a particular narrative through amplification and simplification of complicated political issues as populist parties and leaders do, it is evident that the effects of EU delegitimisation persist. In this perspective, the EU (far from being perfect) continues to be the perfect scapegoat – and the result of blame-shifting – of many populist movements, both for internal causes of the EU and the artificial and biased populist construction. Populist Euroscepticism is a challenge and it can be won only by dosing the independence of nations and strengthening the bond between them at the European level. “If politicisation is weak, […] integration is higher”.[27] More European integration is needed. More integration, which means also less politicisation and thus less polarisation, argues for a “more Europe” position and more possibility to take decisions at the European table.

Sources

[1] Hutter, Swen; Kriesi, Hanspeter. (2019). “Politicising Europe in times of crisis”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 26, Num. 7.

[2] Lavenex, Sandra (2018). “‘Failing forward’ towards which Europe? Organised hypocrisy in the Common European Asylum System”. Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 56, Num. 5.

[3] Hutter, Swen; Kriesi, Hanspeter. (2019). “Politicising Europe in times of crisis”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 26, Num. 7.

[4] Zeitlin, Jonathan; Nicoli, Francesco; Laffan, Brigid (2019). “The European Union beyond the polycrisis? Integration and politicisation in an age of shifting cleavages”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 7, p. 963.

[5] Moravcsik, Andrew (2002). In defence of the “democratic deficit”: reassessing legitimacy in the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 40, Num. 4.

[6] Lavenex, Sandra (2018). “‘Failing forward’ towards which Europe? Organised hypocrisy in the Common European Asylum System”. Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 56, Num. 5.

[7] Zeitlin, Jonathan; Nicoli, Francesco; Laffan, Brigid (2019). “The European Union beyond the polycrisis? Integration and politicisation in an age of shifting cleavages”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 7.

[8] Hiscox, Michael J. (Ed. Ravenhill, John) (2017). Global political economy (Fifth edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[9] Hutter, Swen; Kriesi, Hanspeter. (2019). “Politicising Europe in times of crisis”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 26, Num. 7.

[10] Hutter, Swen; Kriesi, Hanspeter. (2019). “Politicising Europe in times of crisis”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 26, Num. 7.

[11] Müller, Harald (2017). “The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in Jeopardy? Internal Divisions and the Impact on World Politics”. The International Spectator, Vol. 52, Num. 1, p. 20.

[12] Zürn, Michael. (Eds. Carlsnaes, Walter E.; Risse, Thomas; Simmons, Beth A.) (2012). Handbook of International Relations (Second edition). London: Sage.

[13] Zürn, Michael. (Eds. Carlsnaes, Walter E.; Risse, Thomas; Simmons, Beth A.) (2012). Handbook of International Relations (Second edition). London: Sage.

[14] Auel, Katrin; Rozenberg, Olivier; Tacea, Angela (2015). “To Scrutinise or Not to Scrutinise? Explaining Variation in EU-Related Activities in National Parliaments”. West European Politics, Vol. 38, Num. 2.

[15] Auel, Katrin; Neuhold, Christine (2016). “Multi-arena players in the making? Conceptualising the role of National Parliaments since the Lisbon Treaty”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 24, Num. 10.

[16] Hooghe, Liesbet (2001). The European Commission and the Integration of Europe: Images of Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[17] Jensen, Mads Dagnis; Koop, Christel; Tatham, Michaël (2014). “Coping with power dispersion? Autonomy, co-ordination and control in multilevel systems”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 21, Num. 9.

[18] Karlas, Jan (2012). “National Parliamentary control of EU Affairs: institutional design after enlargement”. West European Politics, Vol. 35, Num. 5, p. 1110.

[19] Christiansen, Thomas; Reh, Chrstine (2009). Constitutionalising the European Union. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

[20] Hutter, Swen; Kriesi, Hanspeter. (2019). “Politicising Europe in times of crisis”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 26, Num. 7, p. 997.

[21] Zürn, Michael. (2019). “Politicising Europe in times of crisis”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 26, Num. 7.

[22] Zürn, Michael. (Eds. Carlsnaes, Walter E.; Risse, Thomas; Simmons, Beth A.) (2012). Handbook of International Relations (Second edition). London: Sage, p. 416.

[23] Hix, Simon (Ed. Caramani, Daniele) (2008). Comparative Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 595.

[24] Zeitlin, Jonathan; Nicoli, Francesco; Laffan, Brigid (2019). “The European Union beyond the polycrisis? Integration and politicisation in an age of shifting cleavages”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 7, p. 964.

[25] Hutter, Swen; Kriesi, Hanspeter. (2019). “Politicising Europe in times of crisis”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 26, Num. 7, p. 999.

[26] Zeitlin, Jonathan; Nicoli, Francesco; Laffan, Brigid (2019). “The European Union beyond the polycrisis? Integration and politicisation in an age of shifting cleavages”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 7.

[27] Schimmelfennig, Frank (2018). “European integration (theory) in times of crisis. A comparison of the Euro and Schengen crises”. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 25, Num. 7, p. 975.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of SpecialEurasia. Assumptions made within the analysis are not reflective of the position of SpecialEurasia.