Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 15 Issue 4

Author: Luca Garruba

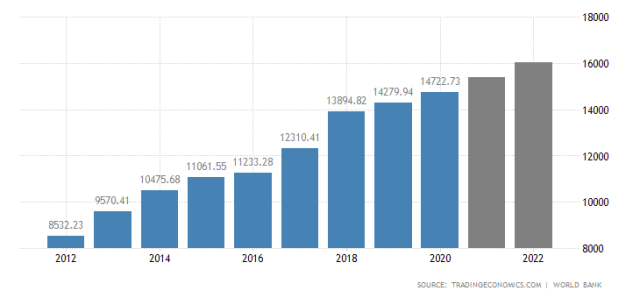

Although China’s economic growth has slowed in recent months due to several COVID-19 outbreaks, energy shortages and a regulatory crackdown in some sectors, the overall economic recovery is stable. Annual GDP growth is expected to reach 8% in 2021, down 0.1 from the July forecast.[1]

In their 2022 China economic forecasting, economists speculate that the Chinese Government could stick to what it said in recent meetings, stabilising the economy through a more accommodative monetary policy and maintaining reasonable liquidity that can provide targeted financial support to small and medium-sized businesses. The Government intends to focus on scientific and technological innovation and green development to stimulate growth in the short term, carrying out the reforms introduced this year in the long term.

Companies operating in China have had to deal with sudden changes in the local market this year as the Government has decided to prioritise socio-economic policy to ensure sustainable and more rational growth.[2]Several new laws and regulations were introduced at short notice, presenting multiple risks and multiple opportunities. For those who invest in China, both individuals and companies, it is always advisable to contextualise every regulation and every Government initiative since all the new regulations are always included in broader programs and always aimed at the long term.

Before presenting Chinese economic forecasting in 2022, it is fundamental to retrace this decidedly eventful 2021 for the Chinese market where the prohibitions of monopoly and anti-competitive practices have been tightened, and dramatic reforms have been imposed on education and other sectors.

China in 2021: a summary

As of 2021, China has entered the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025).[3] The Communist Party of China celebrated its centenary in July and concluded the sixth plenum of the party’s Central Committee in November, which paves the way for the appointment of the following Chinese leadership.

On January 1st, 2021, the country’s first civil code came into effect, followed by a series of new laws, most notably the Data Security Law (DSL) and the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which add regulations linked to the growing regulation on the control of cross-border data flows and on the protection of personal information.[4]

Lawmakers have also begun to revamp antitrust law and crack down on anti-competitive behaviour, in part to curb the sprawling private tech sector, particularly the so-called ‘platform economy’. At the same time, the Government is forcing this sector to abolish the illegal “996” labour policy and improve the employee welfare plan.[5]

Under the pressure of a growing demographic imbalance, China’s top legislature finally amended the Population and Family Planning Act, repealed birth control measures, and legalised the three-child policy. The Government also has a keen interest in the quality of the next generation of China, imposing sweeping reforms in the education sector that have dramatically banned all private for-profit enterprises from teaching compulsory education subjects.

The Government has also long wanted to break the vicious circle of real estate speculation and credit expansion. The latest rules include tighter restrictions on developer financing of homebuyers, giving real estate a significant blow. Meanwhile, China Evergrande, one of China’s largest real estate developers, found itself in a front-page liquidity crisis, followed by Kaisa and other developers.[6]

Within the real estate sector, China introduced a property tax in October. As part of the campaign to reduce a considerable wealth gap and promote “common prosperity,” the National People’s Assembly (NPC) authorised the State Council to implement a pilot property tax scheme in certain regions.

As far as foreign policy is concerned, 2021 saw competition intensify between the United States and China, particularly in the technological, financial, and military arenas. In June, the U.S. Senate passed the American Innovation and Competitiveness Act to compete with Chinese technology, and China passed the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Act to counter-sanctions by the United States and its allies.[7]

Although the two countries leaders agreed to “look” around their bilateral relations, in a virtual meeting in November, the United States continues to blacklist Chinese quantum computing and semiconductor companies. The two powers recently clashed on Wall Street, with US-listed Chinese companies in the geopolitical crosshairs.

Beijing is determined to develop its technological capacity to move up the global value chain, inevitably leading it into conflict with U.S. interests (reminiscent of the US-Japan trade rivalry that lasted from the 1960s to the 1990s).

One of the few areas where the two powers can work together is probably the fight against climate change. During the final days of the COP26 Summit, the United States and China released a surprising joint statement to cooperate on climate issues over the next decade.

At the COP26 summit, China announced its long-awaited action plan to reach its carbon emissions peak by 2030. In September, Chinese President Xi Jinping said China would stop supporting new energy projects at coal abroad. In order to achieve the net-zero carbon emissions goal, China should implement more policies to regulate polluting commodity industries, transport pollution and household waste; as a result, there will be various opportunities in the fields of sustainable energy and environmental protection.[8]

Last year also marked the 20th anniversary of China’s accession to the World Trade Organization. In September, China formally applied to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Trade Agreement for the Transpacific Partnership (CPTPP) and two months later applied to join the Partnership Agreement for the Digital Economy (DEPA).[9]

Tightening of personal data

“Personal data regulation” was undoubtedly a keyword for China in 2021. In the second half of the year, China introduced a series of laws and regulations that tighten control over data:

- On June 10th, 2021, China’s highest legislature, the National People’s Congress (NPC), officially approved the Data Security Law (DSL), which began on September 1, 2021. The law establishes how data should be used, collected, developed, and protected in China.

- On July 10th, 2021, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) began inspecting cybersecurity review measures following the investigation into travel company Didi Chuxing. The measures for the first time propose that any Chinese company, which holds the personal information of a million or more users, should request a government cybersecurity review before being listed overseas.[10]

- On August 20th, 2021, the NPC adopted the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPL), which entered into force on November 1st, 2021. The law strengthens control over the collection and use of personal information and establishes strict rules on how companies should handle this type of data.

- On September 30th, 2021, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technologies (MIIT) developed the Management Measures for Data Security in the Field of Industrial Sectors and Information Technologies. The Measures clarify how companies should manage sensitive industrial and telecommunications data and classify the data into “core”, “important” and “ordinary” categories.

- On October 29th, 2021, the CAC published the draft measures for assessing the security of data export. The measures provide clarification on the government body responsible for overseeing security assessments and on the procedures that companies must undergo to obtain authorisation to transfer data abroad.

- on November 14th, 2021, the CAC released the Network Data Security Management Regulation (Exposure Draft), which unifies the data security rules introduced by CSL, DSL and PIPL and implemented the review requirements for companies that pursue IPO in Hong Kong.

Instruction to understand recent Chinese trends

So far, the three general laws (CSL, DSL and PIPL) together constitute the legal framework for the governance of cyberspace, information security and data protection in China.

The DSL, effective from September 1st, 2021, contains a wide range of provisions relating to data security. Perhaps the essential part is treating “important data”, which generally refers to data relating to security, the national economy, and people’s livelihood. DSL and some other regulations have repeatedly stated that transferring “important data” overseas is subject to government review.

The PIPL, effective November 1st, 2021, is the first Chinese law to precisely regulate the protection of personal information, with a far-reaching impact on corporate data privacy compliance. The crucial point is that for companies that process personal data above a certain amount (established by the CAC) and CII operators, personal information collected or generated within the Chinese territory must be stored within China. If it is necessary to provide data overseas, the company must undergo a security check conducted by the CAC in advance.

As for how the government review will be conducted, the CAC released the long-awaited draft on data export security assessment measures in October, which delves into the procedures companies must undergo to obtain the ” authorisation to transfer data abroad.

Tackling anti-competitive practices

Since November 2020, when China suspended the IPO of Ant Group, Alibaba’s financial arm, regulators have faced a long-simmering problem in the technology sector: anti-competitive practices.

After a four-month anti-monopoly investigation, Alibaba was fined a record 18 billion RMB ($ 2.77 billion). Additionally, fintech giant Ant Group has been requested a wide-ranging rectification, including rectification of its lending practices and improved data privacy protection.[11]

Other internet conglomerates, including Tencent, Baidu, ByteDance, and Didi Chuxing, have also been fined for violating the anti-monopoly law. Smaller internet companies, including foreign-invested firms, have not been immune: for example, in April, UK takeaway platform Sherpas was fined $ 178,000 by the Shanghai market regulator for anti-competitive conduct.

A range of anti-competitive behaviours, such as forced exclusivity agreements, “cash-burning” strategies to gain market share, unapproved merger and acquisition activities that can cause an industry monopoly, misleading advertising and unfair pricing, have been targeted by the market regulator.

As part of the anti-monopoly campaign, China has imposed antitrust guidelines for digital platforms. In addition, a new antitrust office was launched in November, which will be responsible for conducting investigations and supervising merger and acquisition activities and market competition.

Reorienting Education for the Next Generation

To reduce student workloads and promote educational equity, China has embarked on reforms of its education system, including bans on for-profit mentoring in education and the cancellation of written exams in first and second grades.[12]

In July, the State Council released Guidelines to ease further the burden of excessive homework and off-site tutoring for students in the compulsory education phase. These lines provide that:

- Existing institutions that teach school curriculum subjects (from now on “disciplinary training institutions”) must register as non-profit organisations.

- Listed companies are prohibited from financing or investing in disciplinary training institutes through the stock market, nor from acquiring the assets of such institutes by issuing shares or paying in cash.

- Foreign capital is prohibited from investing in disciplinary training institutes through mergers and acquisitions, franchise development.

- No off-site training agency can arrange disciplinary training during statutory national holidays, rest days, winter and summer holidays.

However, while the Government limits foreign investment in academic tutoring for school-age students and increases scrutiny over foreign teachers and imported teaching materials, investors need to be aware that the opportunities still exist: the Government is simultaneously promoting investment and education for private individuals in areas such as vocational education in order to improve the skills of the country’s workforce.

In addition to targeting the education sector, China’s focus on the growth of the next generation has also extended to the online gaming industry. To prevent gambling addiction from harming children’s academic and personal development, China limited the number of time children can devote to video games in August, a blow to the world’s largest online games market.[13]

The journey to net-zero emissions begins

In September 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping promised that China would peak carbon emissions by 2030 and become carbon-neutral by 2060.

In November, ahead of the COP26 summit, China has released its long-awaited action plan to reach the carbon peak by 2030. The action plan lists three important carbon milestones (set for 2025, 2030 and 2060) and ten key tasks in order to achieve the target, which should involve compliance risks for sectors such as coal, petrochemical, chemical, steel, non-ferrous metal smelting, construction and transportation, as well as opportunities in the next decade for energy green and low carbon emissions, green technology and circular economy.

In July, China launched the world’s largest carbon trading market in Shanghai to reduce the growth of carbon emissions. At launch, the carbon market covers more than 2,225 companies operating coal and gas plants to produce energy and heat, but government officials intend to expand that market to other polluting industries as well, including steel, cement, chemicals, and aviation.

Green Finance

Achieving these carbon goals means investing significant amounts of money. It is estimated that nearly RMB 140 trillion (the US $ 22.4 trillion) will be needed over the next thirty years, more than five times the size of the current German economy.

The Government’s strategy is actively promoting green finance, a range of policies and incentives to funnel private-sector capital into green projects and industries, primarily through loans and bonds.

It is adopting various tools for green finance, including making it more attractive to banks. For example, in November, the Central Bank launched its Carbon Reduction Support Facility, designed to provide low-cost finance to financial institutions operating nationwide to channel low-cost business loans to businesses, clean energy, environmental protection, energy-saving and carbon reduction.

In addition, the Government is evaluating ‘green credit’ and ‘green trade’. The Commerce Department recently published the five-year plan for promoting foreign trade, which proposes establishing a “green trade index” and collecting data on the carbon intensity of trade.

Externally, China is also trying to align green finance standards with international best practices. With an eye on cross-border investment, China and the EU finally formulated a jointly recognised standard for green project definition in November to help global channel capital to sustainable businesses in both markets.

Common Prosperity

This year, top Chinese officials have increasingly promoted “common prosperity”. Indeed, this concept underpins many of the necessary decisions of top leaders, including support for small and medium-sized businesses, a regulatory crackdown on tech giants, improved job protection, education reforms, subsidy vocational training, the introduction of tax ownership and the encouragement of charity and donations by wealthy groups and businesses.

Over the next few decades, the country is expected to be more focused on tackling inequality, redistributing wealth (including between regions) and creating more opportunities for upward social mobility.

Undoubtedly, this concept has worried wealthy individuals, deep-pocketed businesses, and some sectors (such as the luxury industry). However, to discourage capital flight, senior officials stressed that shared prosperity does not mean “killing the rich to help the poor” but creating an ever more prosperous and wider consumer pool to increase domestic consumption.

On the second day of the Sixth Plenum, it was stated that development would remain the top priority for China to achieve shared prosperity. This means that common prosperity is about the equitable distribution of existing wealth, the expansion of the country’s wealth, and the growth of the middle class.

Common prosperity is an essential requirement of Chinese socialism and will impact the definition of policies in 2022. Therefore, all the policies and regulations followed in 2021 should not be evaluated in the short term but the long and contextualised in the prolonged program that the Chinese Government is carrying out.

Coping with supply chain disruptions

For China, the supply chain conundrum is thornier and more twofold, with challenges on the logistics and demand fronts and the technology blockages imposed by the United States.

To support its supply chains, Beijing has so far adopted four interlinked strategies: the Dual Circulation Strategy (DCS), internal innovation, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and a legal regime against sanctions.

Foreign investors are concerned that China is trying to replace foreign technology. The country is pushing internal innovation, mainly focusing on some key areas: semiconductors, quantum computing, 5G, biotechnology, artificial intelligence. At the same time, it is trying to build diversified and reliable global supply chains to ensure energy and food supplies.

China in 2022: forecasting

2021 has presented numerous challenges for many companies and investors in China, who have addressed local market developments and systemic concerns plaguing global supply chains exacerbated by the pandemic.

As Chinese politicians focus more on the quality of the country’s development trajectory, looking forward to 2022, the Government should:

- prioritise policies relating to an ageing society;

- ensure that the use of private capital (including foreign capital) is in line with the main development objectives;

- strengthen the resilience and security of industrial and supply chains;

- strengthen control over areas related to national security.

Many of the problems China faced in the second half of 2021 are expected to continue into 2022, with the rising numbers linked to Covid-19, in particular, which could hurt profits earlier this year. At the same time, more targeted development aimed at key areas of the economy will bring more significant opportunities for growth, mainly where those areas help sustain China’s profits in terms of economic stability and people’s livelihoods.

Given the dynamic geopolitical and business climate, understanding China’s development policies and goals is necessary to make timely changes to business development strategies and avoid compliance risks.

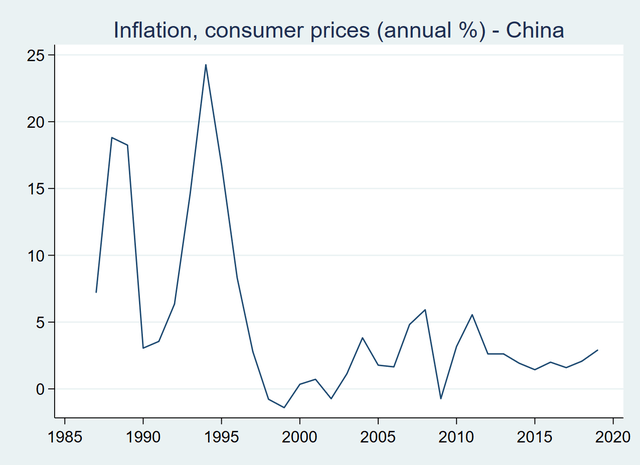

What emerges, however, is the prospect of long-term prosperity that the Chinese Government wants to guarantee the nation. All the last year’s regulations aim to ensure the sustainability of Chinese growth. Therefore, China does not want to destroy itself; all regulations have been passed in line with the Five-Year Plan launched last year, directed at rationalising the Chinese economy to ensure a less impetuous but more constant growth rate over time.

Sources

[1] Silvia Amaro (2021) IMF cuts its global growth forecast, citing supply disruptions and the pandemic, CNBC. Retrieved from: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/10/12/imf-cuts-growth-forecast-as-supply-disruptions-covid-pandemic-weighs.html.

[2]Jesse Turland (2021) China States Economic Priorities for 2022, Emphasising ‘Stability’, The Diplomat. Retrieved from: https://thediplomat.com/2021/12/china-states-economic-priorities-for-2022-emphasizing-stability.

[3] The 14th Five-Year Plan of the People’s Republic of China—Fostering High-Quality Development (2021) Asian Development Bank. Retrieved from: https://www.adb.org/publications/14th-five-year-plan-high-quality-development-prc.

[4] Ryan D. Junck et al. (2021) China’s New Data Security and Personal Information Protection Laws: What They Mean for Multinational Companies, Skadden. Retrieved from: https://www.skadden.com/Insights/Publications/2021/11/Chinas-New-Data-Security-and-Personal-Information-Protection-Laws#:~:text=The%20Data%20Security%20Law%20(DSL,on%20the%20data’s%20classification%20level..

[5] Zoey Zhang (2021) “996” is Ruled Illegal: Understanding China’s Changing Labor System, China Briefing. Retrieved from: https://www.china-briefing.com/news/996-is-ruled-illegal-understanding-chinas-changing-labor-system/.

[6] Erin Mendell (2021) What Is China Evergrande, and Why Is Its Crisis Worrying Markets?, The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/evergrande-china-crisis-11632330764; Scott Murdoch and Samuel Shen (2021) China’s Kaisa struggles for relief from bondholders as default risk looms, Reuters. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/markets/rates-bonds/chinas-kaisa-struggles-relief-bond-holders-default-risk-looms-2021-12-02/.

[7] Jake Harrington, Riley McCabe (2021) What the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act Gets Right (and What It Gets Wrong), Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved from: https://www.csis.org/analysis/what-us-innovation-and-competition-act-gets-right-and-what-it-gets-wrong.

[8] COP26: China agrees to ‘ambitious’ climate action plan with US (2021) Deutsche Welle. Retrieved from: https://www.dw.com/en/cop26-china-agrees-to-ambitious-climate-action-plan-with-us/a-59783112.

[9] High-Level Forum marks 20 years of China’s WTO membership (2021) World Trade Organisation. Retrieved from: https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news21_e/acc_10dec21_e.htm.

[10] Arendse Huld (2021) China Cybersecurity Regulations – What do the New Draft Regulations Say?, China Briefing. Retrieved from: https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-cybersecurity-regulations-what-do-the-new-regulations-say/-

[11] Sun Yu, Tom Mitchell (2021) China’s central bank fights Jack Ma’s Ant Group over control of data, Financial Times. Retrieved from: https://www.ft.com/content/1dbc6256-c8cd-48c1-9a0f-bb83a578a42e.

[12] Kevin McSpadden (2021) China’s education reform creates havoc as students head back to school, South China Morning Post. Retrieved from: https://www.scmp.com/economy/article/3146833/chinas-education-reform-creates-havoc-students-head-back-school.

[13]Chris Buckley (2021) China Tightens Limits for Young Online Gamers and Bans School Night Play, The New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/30/business/media/china-online-games.html#:~:text=China’s%20strict%20limits%20on%20how,under%20government%20rules%20issued%20Monday.

Analysis in media partnership with Paesi Emergenti. It is possible to read the original analysis in the Italian language at the following link: Cina 2022: istruzioni per l’uso.