Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 15 Issue 2

Author: Laura Pennisi

There have been and still are numerous issues affecting relations between Iran and Azerbaijan, many of which systematically contribute to increasing tensions between them. Among these, the question of Karabakh and covert Iranian support to Armenia is one of the most often cited, but also issues related to the Caspian Sea, Iran’s relations with regional and external partners like Russia, Turkey, and the United States, and the nuclear arms race often hit the headlines.

Nevertheless, a less considered factor, often put on the backburner, is the so-called “Azeri question” related to the presence of a sizeable Azeri minority in the country’s northern regions and in direct contact with the border of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Factors like Tehran’s continuous discriminatory policies, geographical and cultural proximity to Azerbaijan and Turkey, undoubtedly a trump card for the two countries, and the political developments related to the recent war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, have contributed to igniting the fuse of nationalism within the minority. All this can have relevant geopolitical implications in the fragile balance of alliances built by Tehran throughout the decades and the likewise fragile relations with its neighbours.

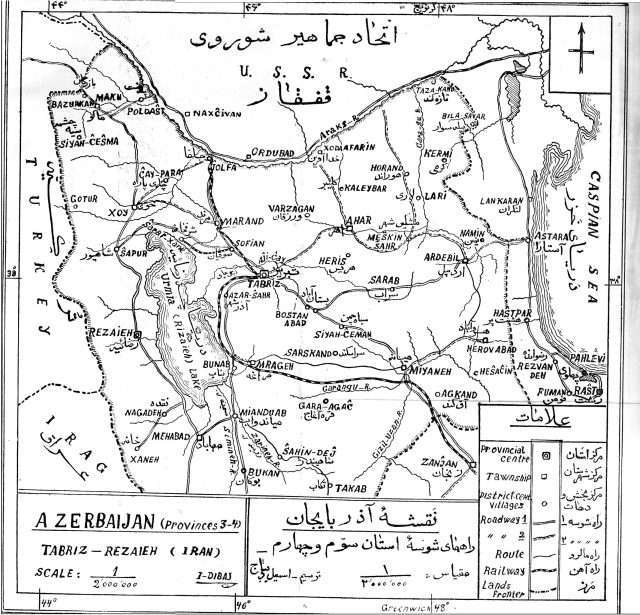

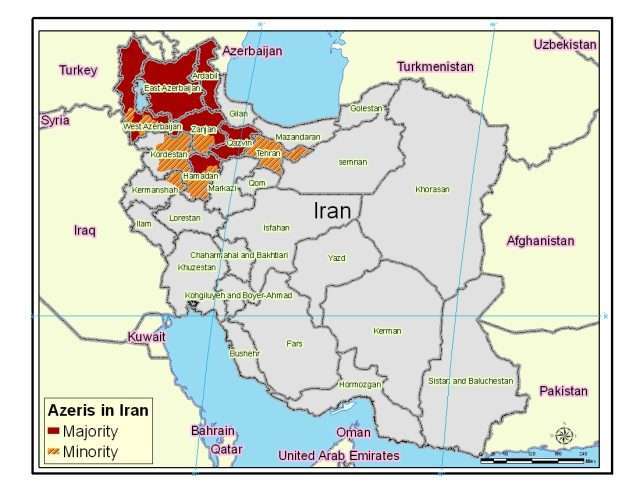

The Iranian Azeri minority in Iran comprises a quarter of the total population of the Islamic Republic of Iran and it is spread in the three northwestern Iranian provinces of West Azerbaijan, East Azerbaijan, and Ardabil.[1] Considered by far the biggest minority in Iran, it used to be also the most assimilated given the long-standing, historically shared religious Shiite tradition. In the past two decades, though, the increased marginalization that repeatedly hit the community, a result of the policies formulated by the elites in Tehran, has reached new heights pushing the minority toward a more nationalistic approach and a rapprochement with Azerbaijan.[2]

The median position occupied by this minority in between two countries finds its answer in history, which explains the reason why Iranian Azeri have retained both Persian and Turkic elements. More precisely, from the 4th century onwards, while the Turkic element prevailed language-wise, the Persian one held on to culture and religion. The strong feeling of integration felt throughout the centuries by this community was strengthened by the powerful Safavid rule from the 16th to the 18th century, founded by Shah Ismail Khatai and originated in the city of Ardebil in Iranian Azerbaijan. Shah Ismail Khatai is also well known for having introduced Shia Islam as the state religion. Later, the Safavid rule was considerably weakened by the Turkic Qajar dynasty and the emergence, in the late 18th century, of a new superpower, the Russian Empire.

The subsequent Russo-Persian wars fought from 1812 to 1813 and from 1827 to 1828, proved highly detrimental for the Safavid Empire as they resulted in two historically relevant treaties: the Gulustan treaty signed in 1813 and the Turkmanchai treaty signed in 1828. The latter determined the destiny of the Iranian Azerbaijanis as they were divided into two areas: Southern Azerbaijan, assigned to the Persian Empire, and Northern Azerbaijan (corresponding to the nowadays Republic of Azerbaijan) to the Russian Empire.[3]

Notwithstanding these historical events that led to politically-based land divisions, the Turkic element has undoubtedly retained a stronger influence on the Iranian historiography, given that during the Safavid rule the Turkish language was actively spoken at the court.[4] This represents until today a thorn for the Iranian government, whose discriminatory policies have considerably weakened the minority’s unwavering support throughout the decades. The 1979 revolution was in fact seen by the Iranian Azeri as an occasion to restore their identity theretofore subjugated by the chauvinist policies of the Shah.

Tehran’s discriminatory policies have repeatedly targeted mainly the minority’s linguistic and cultural rights triggering claims for more autonomy and several unrests that sparked after the government’s outspoken provocations. This was the case in 2006 in Tabriz when a newspaper cartoon depicted Azeri as cockroaches, which triggered protests all over the northern part of the country and for which a link to the U.S. had been suggested by the Iranian government,[5] or in 2009 when the ethnic Azeri Mir Hossein Mousavi fell victim of rigged elections during his run-up to the presidency against the incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.[6] Demonstrations for the reunification of the two Azerbaijan have taken place as of September and October 2006 both in Iran and Azerbaijan asking for more linguistic and cultural autonomy, as happened in the city of Orumiyeh.

This town has been several times in the spotlight for the catastrophe related to the drying up of the Orumiyeh lake, an important source of livelihood for its inhabitants, and with a destiny similar to that of the Aral Sea. Many Iranian Azeri believe that the problem was deliberately ignored by the Iranian authorities to encourage the displacement of the minority to other districts of the country, a practice supported by the parliament’s failure to adopt the necessary measure to prevent the disaster.[7] More recently, during the 2020’s war, many Iranian Azeri showed their support to Baku by protesting in the streets of Tabriz against Tehran’s military support to Armenia demanding the closure of the Iranian-Armenian border through which weapons were transported.[8]

In general, the Azeri language is not only often downplayed by the Iranian authorities through offensive jokes and mockeries of the Iranian Azeri accent, but its use is also prohibited in schools and during festivities, which led many times to arrests and protests.[9] These repressive policies have the side-effect of fueling even further the activities of the National Liberation Movement of South Azerbaijan (NLMSA), based in Baku, and advocating reunification of the Azeri living on both sides of the Araks river, although its political strength appears limited as many of its supporters are systematically arrested and imprisoned.[10]

Tehran’s hostile and discriminatory approach provides its neighbours, Turkey, and Azerbaijan with opportunities to revive strong cultural and economic connections with the minority. The presence of several Turkish satellite channels reminds the Iranian Azeri of their cultural and linguistic vicinity especially on a geographical level due to the incessant exposure to Turkish culture. This acts as a reminder of the minority’s historical Turkic ties that strengthen its self-perception and identity. Throughout the centuries, in fact, the Persian element had been promoted as qualitatively higher than the Turkic one on all levels. Exposure to Turkish culture, though, shows the higher level of social and economic development achieved by Turkey in relation to Iran.[11]

Geopolitical implications

The geopolitical implications of Iran’s unbalanced policies towards this sizeable minority are several. Not only the historical and cultural ties with Turkey and Azerbaijan but also its economic and demographic potential make Iranian Azeri a powerful ethnic and economic barrier for Iran. Their territories, besides being in direct contact with Turkey and Azerbaijan, present the highest number of industrial and trading facilities outside of the capital city[12] which, however, the central government avoids capitalizing on (in theory an obvious solution as the northern regions constitute a natural bridge with Europe).

Investing highly in these territories would be a double-edged sword for Tehran as more economic capacity would run the risk of empowering the minority and its claims, therefore bolstering further its ties with Azerbaijan. This solution, given the recent tensions between the latter and Iran on the morrow of the last year’s Karabakh war, could complicate Iran’s plans to increase cooperation with Armenia for the protection of the Zangezur transit corridor, facilitating in this way Azerbaijan’s projects of infrastructures development to reach the exclave of Nakhichevan.[13] The Iranian-Armenian connections have been already challenged as several episodes were registered since the 2020 November’s agreement on the Azerbaijani-Iranian borders. These regarded detentions of Iranian truck drivers headed towards the southern Armenian cities of Goris and Kapan, which, in turn, degenerated into a large-scale confrontation between Baku and Tehran manifested through military drills and aggressive rhetoric.[14]

It should not be forgotten also that if most of the Armenian gas supplies come from Russia, the rest is supplied by Iran. Maintaining the status quo in the northern regions is, therefore, necessary for Tehran by keeping the Azeri minority as a buffer zone to be handled with the utmost care. This becomes even more imperative considering that the minority is now far more aware of the dynamics that drive the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, which makes tip the balance even more towards Baku. Having millions of Iranian Azeri at Baku’s disposal could give an upper hand over Iran also regarding other alliances, like the long-standing coalition between Azerbaijan and Israel, a country traditionally at loggerheads with Iran.[15]

Another player in this equation is certainly Russia. In the South Caucasus chessboard, it looks like Iran voluntarily refuses to apply any policy that could allow the country to get the upper hand. In the long race to attain nuclear independence, and hunted by U.S. sanctions, Moscow seems to be the only geopolitically reliable partner offering a more efficient diplomatic support and weapons trade. This win-win situation contributed to creating a balanced status quo in the South Caucasus supported by Iran’s cautions defensive policies in the area, limited essentially to U.S. containment. The two fruitless Tehran’s brokered ceasefires in 1992 overwhelmed by Moscow’s fruitful intervention confirm Iran’s weak voice in this matter.[16] This trend has been recently strengthened by the recent meeting in Moscow on October 5th, 2021, between the Iranian Foreign Minister Amir Abdollahian and the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov to discuss developments in the region as Iran expects Russia to manage the threats along the Iranian borders.[17]

In this sense, the Russian peacekeeping mission can serve Tehran’s interests to counterbalance the potentially threatening effects of the Azeri minority in Iran in direct contact with the hot regions. In this, an outstanding role is played also by Turkey and the spectre of Pan-Turkism manifested in northern Iran through soft power’s techniques in support of Ankara’s expansion projects in Central Asia through northern Iran. In this light could also be interpreted the Turkish support to Baku over the development of the infrastructures in the Zangezur corridor, officially endorsed in the November 2020’s agreement at point 9.

The case of the Azeri minority is a telling example of how sizeable communities may indirectly influence a country’s foreign policy. Accordingly, considering the already tense relations between Turkey and Iran due to their role in the Syrian war, Tehran would want to avoid other unrests on its borders. In this sense, Tehran’s accusations against Ankara’s alleged support of Baku during the conflict to reconquer as many territories as possible are not overtly voiced but instead channelled through Russia’s activities in the region. In doing so, Tehran avoids open confrontations with an already unsatisfied minority whose claims could be easily manipulated by the Russian and Turkish sides and be incorporated into the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict. Opting instead for the already established mode of operation with Baku based on a certain degree of cooperation is seen as the best solution, as already shown by the recent gas deal signed by Azerbaijan, Iran, and Turkmenistan in November 2021.[18]

Notwithstanding this, the 2020 war’s outcome can potentially bring about further changes in the regional balance of power as Azerbaijan can see the materialization of the sought-after access to Nakhichevan strengthening, therefore, its alliance with Turkey and leaving Iran even more exposed to a regional precarious situation. In this uncertain condition, fueled also by rampant U.S. sanctions, there is no doubt that milder policies toward the Iranian Azeri minority and some basic recognitions would play a decisive role in stabilizing Tehran’s condition.

Sources

[1]Azerbaijan. Region, Iran. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at https://www.britannica.com/place/Azerbaijan-region-Iran Accessed 2021-12-20.

[2]Iran Azeris. Minority Rights Group International. Available at https://minorityrights.org/minorities/azeris-2/ Accessed 2021-12-22.

[3]Cornell E. S. (2011) Azerbaijan since Independence. New York-London, M.E. Sharpe. P. 7.

[4]Rohrs-Weist P. (2018) Under the Radar: Minorities pose threat to Iranian stability. Global Risk Insights. Available at https://globalriskinsights.com/2018/06/minorities-iran-stability-azeris-kurds/ Accessed 2021-12-27.

[5]Peuch J. (2006) Iran: Cartoon Protests Point to Growing Frustration Among Azeris. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Available at https://www.rferl.org/a/1068797.html Accessed 2021-12-27 Accessed 2021-12-26.

[6]Radio Farda (2018) Reformist Accuses Hardliners of Rigging Contested 2009 Presidential Election. Radio Farda. Available at https://en.radiofarda.com/a/iran-reformist-says-2009-election-rigged-by-eight-million-votes/29583537.html Accessed 2021-12-28.

[7]Najafi A. posted by Femia F. and Werrell C. (2012) Socio-environmental Impacts of Iran’s Disappearing Lake Urmia. The Center for Climate and Security. Available at https://climateandsecurity.org/2012/05/socio-environmental-impacts-of-irans-disappearing-lake-urmia/ Accessed 2021-12-26.

[8] Daily Sabah (2020) Pro-Azerbaijan protestors in Tabriz demand closure of Iran-Armenia border. Daily Sabah. Available at https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/pro-azerbaijan-protestors-in-tabriz-demand-closure-of-iran-armenia-border/news Accessed 2021-12-27.

[9]Iran Azeris. Minority Rights Group International. Available at https://minorityrights.org/minorities/azeris-2/ Accessed 2021-12-22.

[10]Cornell E. S. (2011), p. 323.

[11]Cornell E. S. (2011), p. 322.

[12]Grebennikov M. (2013) The Puzzle of a Loyal Minority: Why Do Azeris Support the Iranian State? Middle East Journal, Vol. 67, No. 1, pp. 64-76. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23361693 Accessed 2021-12-23.

[13]Boltuc S. (2021) Azerbaijan-Iran crisis and Tehran-Yerevan’s new transit route. Geopolitical Report Vol.12(7). SpecialEurasia. Available at https://www.specialeurasia.com/2021/10/16/azerbaijan-iran-crisis-tehran-erevan-transit-route/ Accessed 2021-12-27.

[14]Mnatsakanyan G. (2021) Azerbaijan-Iran tension highlights Karabakh’s energy supplies. Eurasianet. Available at https://eurasianet.org/azerbaijan-iran-tension-highlights-karabakhs-energy-supplies Accessed 2021-12-28.

[15]Vatanka A. (2020) Tehran’s Worst Nightmare. Foreign Policy. Available at https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/10/14/iran-azeri-ethnic-minority-nagorno-karabakh/ Accessed 2021-12-29.

[16]Cornell E. S. (2011), pp. 326-329.

[17]Boltuc S. (2021) Iran-Russia cooperation might support Tehran’s foreign strategy in Eurasia. Geopolitical Report Vol.12(4). SpecialEurasia. Available at https://www.specialeurasia.com/2021/10/06/iran-russia-foreign-policy/ Accessed 2021-12-26.

[18]Kucera J. (2021) Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Iran reach gas trade deal. Eurasianet. Available at https://eurasianet.org/azerbaijan-turkmenistan-and-iran-reach-gas-trade-deal Accessed 2021-12-28.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of SpecialEurasia. More information about Iran-Azerbaijan relations will be discussed on January 27th, 2022, during the Webinar “Geopolitica e conflitti nel Caucaso: sfide attuali e sviluppi futuri”.