Geopolitical Report 2785-2598 Volume 14 Issue 6

Author: Riccardo Rossi

The geostrategic importance that the Japanese Senkaku archipelago has assumed in recent years can be traced back to the geopolitical priorities identified by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the United States, recognisable as the two most militarily equipped countries in the north-west Asia-Pacific area.

With Xi Jinping’s appointment as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) in 2012, the PRC embarked on a wide-ranging programme called China Dream to restore the nation’s leading role in the Asia-Pacific, particularly in the East China Sea. Beijing considers the Senkaku archipelago an area of high strategic value to protect its interests within this geo-maritime space.

In the case of the United States, their geopolitical vision for the Senkaku Islands can be traced back to the foreign policy of the Pivot to Asia, aimed at containing the political-military expansion of the PRC in the Asia-Pacific.[1] Since its presentation, this plan has received the adhesion of various Countries of the Pacific area, among which Japan, even though the sovereign of the Senkaku Islands cannot be considered a primary actor in this framework.

On the whole, the geopolitical priorities identified by Beijing, Washington and the Japanese ally towards the Senkaku have led to an increase of the military presence in the area, focused on obtaining or maintaining a determined political-strategic balance.

Geostrategy and military competition for control of the Senkaku Islands

Within the Northwest Asia-Pacific area, the majority of Sino-US geopolitical attention is directed towards a restricted area of the East China Sea, including the island of Taiwan,[2] the Miyako Channel and the Senkaku archipelago, which is disputed between the People’s Republic of China and the United States.

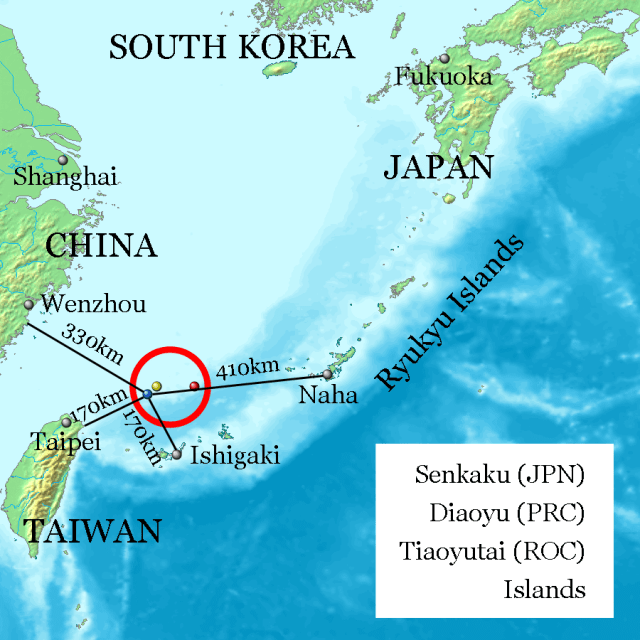

One possible explanation for this Sino-US clash for control of the Senkaku is the islands’ intermediate position between the Chinese coastal segment and the first island chain and their proximity to Taiwan and the Miyako Strait.

Because of this particular location, the Senakaku archipelago is considered by Beijing, the United States and its Japanese ally to be a geo-maritime area of great strategic importance, influencing them to define their respective geopolitical objectives and consequent military doctrines.

With the election of Xi Jinping as Chinese president in 2013, the PRC embarked on a wide-ranging programme called China Dream, aimed at increasing its politico-military influence in the Asia-Pacific region, with a particular focus on the Senkaku Islands to fulfil two geopolitical priorities.

The first is due to the proximity of the Chinese coastline to the Senkaku (330 km), a proximity that Beijing intends to exploit through the construction of a radar detection station on the island of Uotsurijima (the largest in the archipelago, 3.6 km2) in order to increase the effectiveness of its air defence system against any U.S. military operations launched from their bases in Japan and Guam.[3]

The second geopolitical priority identified by President Xi for the Senkaku archipelago is to maintain a constant military presence in the area to supervise both the maritime lines of communication that cross the Chinese Sea and exploit the oil resources present in the depths of the East China Sea.[4]

The combination of these two geopolitical pre-eminences has required Beijing to develop a military doctrine for the Senkaku that combines the development of new weapon systems with the tactical exploitation of the bases located along its coastal segment between the Shandong Peninsula to the north and the coastal strip parallel to the Island of Taiwan to the south.

Through the optimisation of these military areas, the People’s Republic of China has improved the operability of its armed forces, increasing the number of maritime patrols and air raid missions in the geo-maritime area of the East China Sea, including Taiwan Island, its strait, the Miyako Channel and the Senkaku archipelago.

In the case of the Senkaku, the Chinese presence responds in the immediate term to the need to hinder Japanese-US access to the islands, while in the medium to long term, the Xi presidency plans to impose its sea control in the waters close to the archipelago, to prevent the U.S. Seventh Fleet and its Japanese ally from entering this geo-maritime space.[5]

This increase in Chinese military activities in the East China Sea has been identified by the United States and its ally Japan as a severe threat to the geopolitical stability of the Asia-Pacific region. This assessment led the Obama administration in 2011 to present a specific foreign policy programme for this area called Pivot to Asia, confirmed by the subsequent Trump and Biden Presidencies, aimed at containing Beijing’s assertiveness within the geo-maritime space between the Asian coastline and the first island chain.[6]

The implementation of this programme required the White House, in agreement with the Pentagon, to draw up a strategic doctrine that would enhance its bases in Korea and Japan, which were considered indispensable for maintaining sea control on the island of Taiwan, the Miyako Canal and the Senkaku archipelago.[7]

Within this space, the manoeuvres planned by the U.S. Navy, Air Force and Army were supported by the Japanese Presidency of Shinzō Abe (2012-2020), who, with the publication in 2013 of the National Security Strategy, presented his foreign policy line for the Asia-Pacific. In the document, the Abe Government acknowledged Washington’s role as a guiding state in the implementation of the Chinese containment line, but at the same time identified the Senkaku archipelago as a geo-maritime area of great interest because it is rich in fossil resources and the bridgehead of the Sea lines of communications (SLOC) connecting Tokyo to Taipei.[8]

This assessment led to the drafting of a military doctrine that provided for both an increase in the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) budget and the enhancement of the bases located on its territory to maximise the JSDF‘s operational capabilities.

An example in support of this last point can be considered the reorganisation of the command and control system of the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF), to face both the increase of the Russian military presence in the Kuril archipelago,[9] and the growing assertiveness of Beijing towards the Island of Taiwan, the Straits of Miyako and the Senkaku archipelago.[10]

For the latter case, Tokyo has reinforced the Southwestern Composite Air Defense, which, as summarised by Lyle J. Morris in his text The New ‘Normal’ in the East China Sea, resulted in:

«[…] 2014 the JASDF established a new permanent squadron of E-2C Hawkeye AEW aircraft on Naha Air Base off Okinawa to increase early warning detection of foreign aircraft and vessels. These aircraft will complement the new squadrons of Lockhead Martin F-35A fighters to be delivered and deployed in Japan over the coming years.». [11]

In addition to this operation, the Abe government’s decision to strengthen the Japan Coast Guard (JCG) base, located on the island of Ishigaki, where 12 ships equipped with 76 mm cannons are stationed, to which the task of patrolling the waters of the Senkaku archipelago has been delegated.[12]

Conclusions

These concluding notes will summarise the main aspects explaining why the Senkaku archipelago is the subject of geopolitical contention between the PRC and the Japanese-U.S. allies.

An initial reason for this is the unanimous recognition by the three states of the geostrategic importance of the Senkaku, due both to their location and the presence of large quantities of oil in the surrounding waters. This respective attribution of importance is an influencing factor in defining the respective conflicting political-strategic goals.

The PRC attaches great importance to the Senakaku to defend its economic interests and territorial claims. The identification of these interests has required Beijing to increase its military presence in the archipelago, with the immediate aim of hindering the Japanese and American presence, and in the years to come to impose its sea control to prevent the U.S. Seventh Fleet and Japanese armed forces from accessing this geo-maritime area.

In turn, the United States, to contain Chinese assertiveness in the Asia-Pacific, has implemented the Pivot to Asia project aimed at limiting Beijing’s rise within the so-called first island chain. In this project, Washington has considered precious the Japanese political-military support in maintaining sea control of the geo-maritime areas claimed by Beijing, such as the island of Taiwan, the Miyako channel and the Senkaku archipelago, to which Japan holds sovereignty.

In the specific case of the Senkaku, there is a rapid process of militarisation of the surrounding maritime space due to increasing Sino-US tensions for control of the island of Taiwan.

This observation allows us to see that the Senkaku archipelago and Taipei represent the two principal areas of geostrategic instability in the East China Sea, where the risk of a political-military clash between Peking and the Japanese-U.S. allies is higher.

Source

[1] Schiavenza. M (2015) What Exactly Does It Mean That the U.S. Is Pivoting to Asia? And will it last?, The Atlantic.

[2] Rossi, Riccardo (2021) Il confronto militare sino-statunitense per il controllo dell’isola di Taiwan, Geopolitical Report, Vol. 13(1), SpecialEurasia. Retrieved from: https://www.specialeurasia.com/2021/11/02/il-confronto-militare-sino-statunitense-per-il-controllo-dellisola-di-taiwan/

[3] Rossi, Rossi (2021) The geostrategic importance of the Island of Guam in the U.S. policy of containment of Chinese expansionism in the Asia-Pacific, Geopolitical Report, Vol. 14(1), SpecialEurasia. Retrieved from: https://www.specialeurasia.com/2021/12/01/geopolitics-guam-united-states/.

[4] Dossani. R, Warren. S (2016) Harold Maritime Issues in the East and South China Seas, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica.

[5] Micallef. S (2017) Militarisation in East Asia Considerations from the Works of Thucydides and Alfred Thayer Mahan, Anchor Academic Publishing.

[6] Ibid

[7] Rossi, Riccardo (2021) Geostrategy and military competition in the Pacific, Geopolitical Report, Vol. 10(1), SpecialEurasia. Retrieved from: https://www.specialeurasia.com/2021/08/06/geostrategy-pacific-competition/.

[8]Burke. E, Heath. T, Hornung. J, Logan Ma, Lyle J. Morris, Michael S. Chase (2018) China’s Military Activities in the East China Sea Implications for Japan’s Air Self-Defense Force, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California.

[9] Rossi, Riccardo (2021) The geostrategic role of the Kuril Islands in the Russian foreign policy for the Asia-Pacific Northwest area, Geopolitical Report, Vol. 14(4), SpecialEurasia. Retrieved from: https://www.specialeurasia.com/2021/12/14/geostratey-kuril-islands-russia/ .

[10] Ibid

[11] Morris, Lyle J. (2017) The New ‘Normal’ in the East China Sea, RAND Corporation. Retrieved from: https://www.rand.org/blog/2017/02/the-new-normal-in-the-east-china-sea.html.

[12] Ibid