Geopolitical Report 2785-2598 Volume 14 Issue 5

Author: Lorenzo Somigli, Elia Elias

Two countries, a long friendship, a common sea, similar problems: the same exit strategy? Lebanon and Italy have many common traits and some clear differences. Both are centralised countries with marked differences between territories, both are experiencing a long-term political-institutional deadlock and are wondering how to get out. According to Elie Elias and Lorenzo Somigli, one way out could be the large devolution of power to local territories and communities. The implementation of a local and bottom-up model could reinvigorate the relationship between the individual/citizen and institutions and improve the transparency and effectiveness of the decision-making process.

General overview: a global need for autonomy

More and more countries across the planet, over the past thirty years, initiated an articulated decentralisation process. In many cases, like Spain or Belgium,[1] the localistic changeover was the only way to save the unity of state freezing re-emergent local, ethnolinguistic, religious fractures and giving to territories complete representativeness. Germany[2] has adopted the federal formula to hold the Hanseatic, Prussian, and Bavarian souls together, also facing the complex soldering between the two Germanies.

Why devolution? Devolution arises from awareness: there isn’t a real centre, there are peripheral centralities. The centre of legitim power can release decisions or imperative commands, but communities and individuals exist independently. Molecular relationships and ordinary practices are stronger than any central power, enabling to standardise exceptions and variables. Social facts are much more lasting than institutions, according to Braudel.[3] Individuals have rights by nature even without the state.

Consequently, federalism is an interesting model because assembles a large devolution in favour of all the territories with a strong figure like the President, territories can elaborate and implement autonomous policies but there are general and common guidelines. No one can subdue the other, no power can crush the other. Check and balance is the guiding star. It also guarantees speed of decision and versatility, crucial in a globalised world, and, by its nature, is a flexible model tailored to local needs and specificities.

Affinity and differences: a proposal of comparison

Lebanon and Italy claim a centuries-long story of friendship since the time of Fakhr al-Dihn II but also share similar criticalities.[4] Sluggishness, inefficiency, opaqueness in the decision-making process frustrate faith in democratic institutions and fuel anti-politics. Both experienced a forced centralisation, on the example of France, after centuries of municipal and regional self-government: in Italy because of the Unification (1871) completed by Savoy, in Lebanon during the protectorate after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. Both are at the centre of global interests and expansionist aims. Both, especially post-1989, tried to reform the polity in a less-centralised way but the process was incomplete and the results in many cases unsatisfactory. In Lebanon and Italy, at the lower administrative levels, there are forms of local powers that guarantee speed and transparency. There are also many differences between those countries. Lebanon was a unique example of coexistence between numerous religious confessions, while Italy is a Catholic nation that launched a rising religious pluralism after the review of Concordat. Empowerment of territories could be the way to write off the lack of accountability and confidence maybe with varying degrees.

Italy, a country aspiring to be federal stopped in midstream

The complex process of unification

“Una d’arme, di lingua, d’altare,

Di memorie, di sangue e di cor”

A. Manzoni, “Marzo 1821”

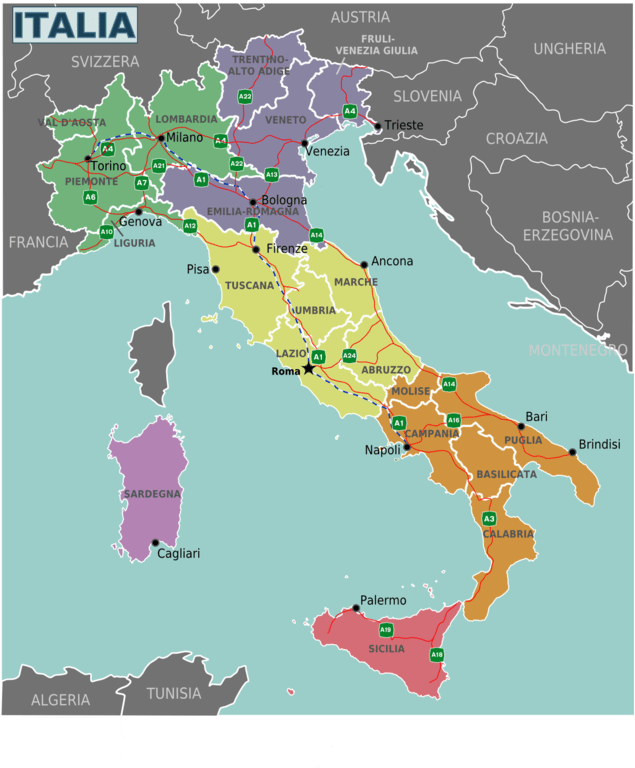

The Italian people exist. Italy exists geographically for centuries, since the time of Augustus when the emperor defined administrative areas that still now form the Italian regions like Aemilia, Apulia, Latium, and Liguria. The Catholic religion, especially after the Concilium of Trento, guaranteed social stability and preserved Italy from religious war. Beyond the variety of dialects, the Italian language is crystallised via literature. However, the Italian nation is just a recent invention.

Geopolitical upheavals, great economic interests, and the exuberance of the Savoy – grew up in the interspaces of the great European powers – facilitate the creation of the Italian nation in the 19th century, which was for centuries a land of conquest for European forces. The landing of Garibaldi in Marsala (Sicily), covered by the English gunboats, marks the end of one of the most advanced kingdoms, the Kingdom of Naples, a strong maritime opponent, and scores the definitive victory of the Kingdom of Sardinia. The Vatican falls shortly after.

The subsequent unification process is uneasy: some territories are annexed while others like Tuscany (1860) or Veneto (1866) voted [5] – there are many frauds – to join the Savoyard Reign. The Italian unification is not a bottom-up process with grassroots participation, is a progressive annexation. There are also many phenomena of strong and violent rejection like Brigandage in the South. Meanwhile, different political figures – right-wing, left-wing, socialists (Salvemini),[6] catholic (Don Sturzo),[7] anarchists, communists – take a stand for devolution.

The conquest of Rome (1871) spells the end of the temporal power of the Catholic Church and opens a large fracture in most of the Italian population. The Catholic population is formally invited by the Pope[8] to not participate in public life undermining the unity project. The following years are marked by a radical secular contrast against religion, with the aim of enfranchising Italians from Catholicism. This raising radicalisation opens a chasm recomposed only by the Concordat (1929), reviewed in 1984.

Italy presents many divisions and fractures. The industrialised North tends to Mitteleuropa while the South is totally Mediterranean, in the middle the “Third Italy” composed of small-medium town and manufacturing districts inheritor of the artisanal tradition. Some cities like Venice and Genova practised the model of marine republics. The North is captained by Milan, the “capital of labour” in opposition to Rome: real country versus legal country. Sicily is the heart of the sea and divides the “two Mediterraneans”.

The progressive annexation by the Kingdom of Sardinia without the involvement of masses, the fraudulent plebiscites, the destruction of the Kingdom of Naples, one of the more advanced, the offence to the Catholic faith: these incongruities undermine the sense of belonging in the nation and leave a deep wound in the Italian people. After the Unity, the Savoyard Monarchy adopts a strictly centralised system on the example of France and extends the Constitution of Reign of Sardinia, the Statuto Albertino to all the new reign.[9]

The slow implementation of the Constitution

Italy, in the Twenties, experienced a drastic shrinkage of freedoms. Fascism, with the support of Monarchy, enters the Institutions of Liberal State and transforms it into a totalitarian one. Two decades of fascist orthodoxy erase every expectation of subsidiarity: no more regional constituencies, no more local powers, majors nominated by the central power, and loyal to the regime. It’s a traumatic experience for Italy that even today bears the scars.

In direct opposition to this complete centralisation, the new Constitution entered into force on the 1st of January 1948 incorporated localist requests. Article 5 states:

“The Republic, one and indivisible, recognises and promotes local autonomies; it implements the widest administrative decentralisation in services that depend on the state; it adapts the principles and methods of its legislation to the needs of autonomy and decentralisation.”

The new constitution recognises the ethnolinguistic minorities, heavily penalised during the fascism, and establishes twenty ordinary regions (art. 131) and some “special statute” regions (Sicily, Sardinia, Trentino, Friuli-Venetia-Giulia, and Valle d’Aosta). However, the implementation of the ordinary (basic law) regions dates to the 1970s and it’s due more to petty political reasons than to a real trust in devolution utility.

That’s exactly why the capability of regions to influence and produce policies remains cumbersome. Regions do not have real power; they can adapt the rules produced by Rome which dictates the general framework and the stakes. The regions take resources from the citizens, send them to Rome, which transfers part of them for the regional services. The result is a regulatory conglomerate and distrust in politics.

’90: the resurfacing of territories and the incomplete reform

The 1990s are a decade of radical change. The fall of the Berlin wall discloses new issues and breaks the Cold War equilibrium. The Italian political system, based on the primacy of DC (Catholic Democracy) in opposition to PCI (Italian Communist Party) collapsed, and territories, on the push of globalisation and European integration, reclaimed more autonomies.[10] The request for large devolution is promoted especially by the northern regions like Veneto and Lombardy, one of the Four Motors of Europe. The request stems from the idea that the unproductive central state devours resources from thrifty territories without giving back services. More autonomy can upgrade the standard of democracy and recompose the chasm between politics and citizens.

Following the incumbent pressure from the territories (in some cases some regions have threatened to secede), at the end of the 90s, there is a phased concession of autonomy by the central government, especially in terms of lawmaking and administrative competencies. The reform of the Fifth Title of the Constitution (2001) is the culmination of the process and marks a significant step towards greater participation of all the territories (regions, provinces, municipalities, mountains authorities) whose role is fully recognised. The biggest novelty of this reform is the variation in the field of legislative competencies: some matters are in the “exclusive competence” of the central state, some of “concurrent competence” between the state and the regions.

The modified art. 117, third comma, states: Matters of concurrent legislation are: international relations and relations with the European Union of the Regions; foreign trade; job protection and safety; education, without prejudice to the autonomy of educational institutions and with the exclusion of education and vocational training; professions; scientific and technological research and support for innovation for the productive sectors; health protection; Power supply; sports regulations; civil protection; the government of the territory; civil ports and airports; large transport and navigation networks; ordering of communication; national energy production, transport, and distribution; complementary and supplementary pension; coordination of public finance and the tax system; enhancement of cultural and environmental assets and promotion and organisation of cultural activities; savings banks, rural banks, regional credit companies; regional land and agricultural credit institutions. In matters of concurrent legislation, the legislative power is vested in the Regions, except for the determination of the fundamental principles, which is reserved for the legislation of the State.

The reform introduces a clear principle of subsidiarity: regions have the power to intervene in regulatory gaps. The reform is inspired by a federalist vision for the European Union which, in the intentions of the promoters, had the objective of favouring exchange, direct interaction between the regions of Europe, and the sharing of best practices. The project of a federal Europe has remained a dead letter, but efficient territories started cooperating.

This devolution enables some virtuous regions to emerge reaching a European level in terms of quality of services, especially in the health sector but also sharpens the inequality between North and South. After the reform, some regions take flights and often anticipate state legislation. However, there is a flourishing of laws, often different from North to South, which penalises all the Italian system.

Now Italy has an asymmetric and dysfunctional regionalist system. The regions with special status remain intact. Same virtuous regions reached an international standard. Others failed and are seen by citizens as just an additional expense. Anyway, after the reform of V Title, there was an attempt of federal reform (2006) without success, but also a contrary attempt to revoke powers devolved to regions (2016), also unsuccessful.

Although, the issue of territories remains unsolved. The devolution of legislative powers is the best that could be achieved without changing the Constitution from the ground up (in Italy is said “federalism with the unchanged Constitution”). Now Italy is a less-centralised country with some important powers devolved to local organisms, but the process of devolution is incomplete and the application cumbersome: Italy is stopped in the midstream.

Differently from Lebanon but also from Belgium or Spain, Italy hasn’t ethnic, religious, linguistic fractures. There was an incongruent unification and there were some traumatic ruptures, but Italian unity has a real basis. A federalist adjustment could be a natural – not radical reform – to improve accountability and solve the long-standing contradictions in Rome-territories relationships.

Localism isn’t a return to past Italy, isn’t a disruption of the much-needed unity: it’s a way to correct relevant mistakes in the unification process. So, localism could ameliorate the administration and strength the unity. The centralisation model was the product of the time: it had successes and incongruities, now problems, instances, and global perspectives call for a new solution.

Sources

[1] Art.1 of the Constitution (1993) states: “Belgium is a federal state composed by communities and regions”. There are Regions and Communities: a mixed example of federalism.

[2] Cf. Gunlicks A. (2003). “The Länder and German federalism”, Manchester University Press.

[3] Braudel F. (2001). “Les mémoires de la Méditerranée”, Le Livre de Poche.

[4] The Druze Emir Fakhr al-Dihn (1572-1635) is considered one of the founders of the modern Lebanon. After trying to establish an anti-Ottoman alliance, he takes refuge in Tuscany.

[5] Universal male suffrage.

[6] Gaetano Salvemini (1872 – 1957) was the promoter of a “centrifugal federalism”. His reflection stems from the awareness that administrative and financial centralisation after the Unity severely damaged the South. Cf. Luccese S., Federalismo, socialismo e questione meridionale in Gaetano Salvemini, Taranto, Laicata (2004).

[7] Don Luigi Sturzo (1871 – 1959), the founder of the Popular Italian Party, embraced the Meridionalist ideas and focused on the role of Municipalities.

[8] Reference is made to the “non expedit” provision issued by Pope Pius IX, advising Catholics not to participate in political life. Subsequently, the Holy See clarified that it was a prohibition. The provision remained formally in effect until 1919.

[9] The Statuto Albertino (1848) is a classic example of an octroyed constitution, conceded by the Kings to subjects. The Statute could be modified with ordinary law and its voids, its silences – as Italian academics say – opened the doors to fascist totalitarianism.

[10] Cf. Woods D., Regional ‘leagues’ in Italy: the emergence of regional identification and representation outside of the traditional parties, “Italian politics”, Istituto Cattaneo (1992).

Bagnasco A. (1977). “Tre Italie – La problematica territoriale dello sviluppo italiano”, Il Mulino (Bologna).

Torchia L. (2002). “Concorrenza fra Stato e Regioni dopo la riforma del Titolo V: dalla collaborazione unilaterale alla collaborazione paritaria”, Le Regioni, Il Mulino (Bologna).

Mastromarino A. (2010). “Il federalismo disaggregativo. Un percorso costituzionale negli stadi multinazionali”, Centro Studi sul Federalismo.

Cassese S., (2012). “The Italian constitutional architecture: from unification to the present day”, Journal of Modern Italian Studies.

Marchetti G. (2021). “Le conflittualità tra Governo e Regioni nella gestione dell’emergenza Covid-19, i limiti del regionalismo italiano e le prospettive di riforma”, Centro Studi sul Federalismo.

*This paper was divided into two parts. The first one presents a general overview of the research and the analysis of the Italian cases. The second part, which we will publish soon, will analyse the Lebanese case.