Geopolitical Report 2785-2598 Volume 14 Issue 2

Author: Uran Botobekov

Amid the burgeoning sentimental relationship between Beijing and the resurrected Taliban’s Emirate 2.0, the al Qaeda-affiliated Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP) has aggravated its propaganda war against Communist China, cleverly concealing its historically faithful jihadi bonds with the Afghan Taliban. Beijing is building up its military presence in post-Soviet Central Asia despite the Taliban’s assurances of non-interference in China’s internal affairs. One example is its establishment of military bases in the Af-Pak-China-Tajik strategic arena near the isthmus of the Wakhan Corridor in Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan province.

Although China did not camouflage its contentment with the failed U.S. policy in Afghanistan and sought to leverage the Taliban victory as its foreign policy asset,1 Beijing has faced the Taliban’s elusive stance in curbing the Uyghur jihadists challenges. Today, the Celestial is well conscious of its harsh realities. With the withdrawal of the U.S. forces from Afghanistan, Beijing lost a safe buffer zone in the strategically critical Afghan-Chinese borders area in Badakhshan, which has afforded a free secure area for over 20 years. While the U.S.’s presence in the region disturbed China, it provided Beijing with relative stability and protected from infiltrating global al Qaeda elements into the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Therefore, by showcasing its concern over its instability in the neighbouring country, Beijing prefers to pressure the Taliban on security matters,2 claiming that Afghanistan should not become a safe haven for terrorist organisations such as the Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP). On October 25th,2021, during the bilateral meeting in Qatar’s Doha, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi pressed Taliban’s Acting Deputy Prime Minister Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar and Acting Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi to make a clean break with Uyghur jihadists of TIP and to prevent Afghanistan from becoming a hotbed of global terrorism.3

The Taliban’s Interim government is accustomed to responding to such external pressures from its neighbours and the international community. The typicality of its response lies in the denial of the presence of Central Asian and Uyghur terrorist groups on Afghan soil, further wittily dodging the topic of its ties with al Qaeda. Taliban strategists seeking international recognition have apparently developed cunning tactics to carefully conceal their ties to al Qaeda and Central Asian jihadi groups while maintaining the bayat (oath of allegiance) of veteran strategic partners in holy jihad.

Furthermore, this time, Taliban representative Suhail Shaheen voiced a stock answer,4 stating:

“many Uyghur fighters of TIP have left Afghanistan because the Taliban has categorically told them there is no place for anyone to use Afghan soil against other countries, including its neighboring countries.”

Nevertheless, the Chinese authorities are well aware of the Taliban’s insincerity on this matter. In turn, the Taliban realised that the authorities of China and Central Asian states did not believe their statements. Consequently, Beijing denied the Taliban’s claims,5 demanding that approximately 200-300 Uyghur militants of TIP currently live in the Takhar province near Baharak town.

Certainly, to calm Chinese concerns and encourage deeper economic cooperation with Beijing, the Taliban has removed TIP Uyghur jihadists from the 76-kilometre Afghan-China border area in Badakhshan to the eastern province Nangarhar in early October.6 The Taliban’s double-play testifies their walk on a fine line between pragmatism and jihadi ideology, especially when they simultaneously want to look like a state and maintain a historical relationship with al Qaeda.

A short look at Taliban-China relations

Since the mid-1990s, the Af-Pak border arena has remained central to China’s security and counterterrorism strategy.7 Chinese policymakers were concerned that the TIP’s Uyghur militants found refuge in Afghanistan’s border region of Badakhshan and are waging a decades-old holy jihad to liberate Eastern Turkestan from the iron claw of Beijing. Within this framework, China’s counterterrorism policy aims to prevent the challenge of the TIP Uyghur jihadists who have been deeply integrated into global al Qaeda’s structure over the past quarter-century. This undertaking surfaced on Beijing’s agenda since the collapse of the pro-Moscow regime of Mohammad Najibullah in 1992 and became highly acute after the Taliban’s lightning seizure of power in August 2021.

In order to break the long-standing and trusted jihadi ties between TIP and the Taliban, Beijing has emerged as a pragmatic backer of the Taliban’s new rule, promising economic and development support through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).8 For its part, the Interim Afghan government, seeking international recognition, has called China the most important partner and pushed for deeper cooperation with Beijing.9

Following the steps of its historical diplomacy of flexibility and pragmatism from the Qing dynasty, Beijing has forged a pragmatic and operative relationship with the Taliban for nearly thirty years. Since the Taliban’s first rise to power in 1996, this pragmatic relationship has been centred on China’s counterterrorism strategy. Guided by the Art of War strategy of the ancient Chinese philosopher Sun Tzu, Beijing decided to “defeat the enemy without fighting”. In 1999, China launched flights between Kabul and Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang Uyghur region, and established economic ties with the Taliban who patronised Uyghur militants of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM – now TIP).10

In December 2000, China’s Ambassador to Pakistan Lu Shulin met with the Taliban’s founder leader Mullah Omar in Kandahar, in which Lu voiced Beijing’s position on the need to stop harbouring Uyghur jihadists operating in Afghanistan.11 Consecutively, the Taliban anticipated that China would recognise their government and prevent further U.N. sanctions. During the meeting, Mullah Omar assured Lu that the Taliban “will not allow any group to use its territory for any activities against China.”. However, this deal was only half materialised. While Omar did restrain Uyghur jihadists from attacking China’s interests in the Af-Pak zone, he did not expel them from Afghanistan. Moreover, Beijing did not oppose new U.N. sanctions against the Taliban, it only abstained.

Following the collapse of Mullah Omar’s so-called shari’a regime after 9/11, China did not sever its ties with the Taliban leaving room for strategic change in the future. Putting eggs in different baskets, in 2014-2020, China secretly hosted Taliban delegations in Beijing several times and provoked them to struggle against foreign invaders for the country’s liberation actively.12 However, China’s central focus in their contacts with the Taliban has always been to curb the Uyghur jihad against the Celestial and build the first line of defence in the Wakhan Corridor along with the Af-Pak-China-Tajik strategic arena.13

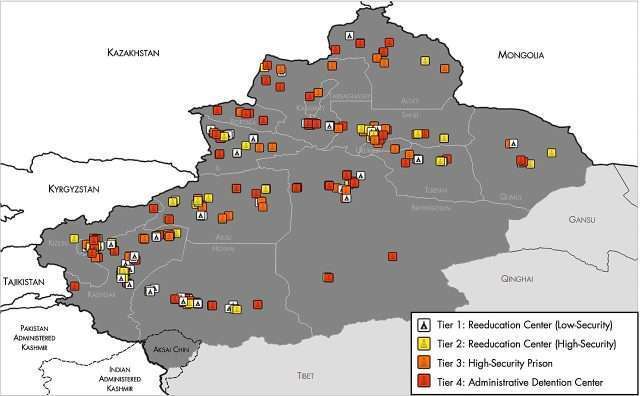

Hence, according to China’s Counter-Terrorism Strategy, securing BRI strategic projects overseas from TIP attacks and blocking the Salafi-Jihadi ideology in Xinjiang became even more critical for Beijing since the Taliban overtook the power. Counterterrorism and concerns of Islamic radicalisation were the justification for China’s crimes against humanity in Xinjiang, where the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has imprisoned more than 1.5 million Uyghurs, Kazakhs and Kyrgyz Muslim minorities in concentration camps, manically depriving them of their religion, language and culture since 2014.14

China’s military footprint in Central Asia

Predictably, the abrupt U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan encouraged Beijing to continue its aggressive and assertive foreign policy toward Central Asia to expand its BRI projects in the region. If before, in exchange for its economic assistance, Beijing demanded from Central Asian nations to adhere to the “One-China policy” (recognition of Taiwan as part of PRC) and support its war against “three evils” (separatism, religious extremism and international terrorism), then now it is also stepping up the military footprint in the region.

On October 27th,2021, the Tajik Majlisi Namoyandagon (Lower House of Parliament) approved China’s proposal to construct a $10 million military base in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province near the intersection of the Af-China-Tajik borders arena. The agreement reached between Tajikistan’s Interior Ministry and China’s Public Security Ministry indicates the new base would be owned by the Rapid Reaction Group of the Interior Ministry.15

This is not Beijing’s first overseas military base in Central Asia. China already operates a military base located 10 km from the Tajik-Afghan border and 25 km from the Tajik-Chinese border in the Tajikstan’s Gorny Badakhshan province on the isthmus of the Wakhan corridor. Thus, the Chinese base overlooks a crucial entry point from China into Central Asia, Afghanistan and Pakistan.16 In accordance with secret agreements signed in 2015 or 2016 between China and Tajikistan, Beijing has built three commandant’s offices, five border outposts and a training centre, and refurbished 30 guard posts on the Tajik side of the country’s border with Afghanistan.17

In July 2021, the Tajik government offered to transfer complete control of this military base to Beijing and waived any future rent for military aid from China. The Chinese military base in Tajikistan has no regular troops of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) but has representatives of the People’s Armed Police (PAP). It is worth pointing out that China, concerned about the activities of TIP’s militants in Xinjiang and their potential links with transnational terrorism, adopted the first counterterrorism legislation on December 27th, 2015.18 The law provides a legal basis for various counterterrorism organs, including the PAP, empowering it with broad repressive functions. PAP members currently serve at China’s overseas military base in Tajikistan, the primary function of which is counterterrorism monitoring of Tajik-Af-Pak border movements.

It is imperative to note that China is concentrating its military facilities not in the depths of Tajik territory but precisely on the isthmus of the vital Wakhan corridor at the Af-Pak-China-Tajik borders intersection. In the mid-90s, Uyghur militants fled China’s brutal repression via the Wakhan corridor to join the Taliban, al Qaeda and TIP in Afghanistan. In their propaganda messages, TIP ideologists often mention the Wakhan Corridor as a “Nusrat (victory) trail” through which the “long-awaited liberation of East Turkestan from the Chinese infidels will come.”

The mastery of the Af-Pak-China-Tajik strategic arena is currently critical to Beijing for several reasons. First, holding the Wakhan Gorge allows China not to depend solely on the will of the Taliban to prevent attacks by Uyghur jihadists of TIP. Secondly, it gives China an additional lever of pressure on the Taliban to sever their ties with Uyghur militants, playing on the contradictions between Tajikistan and the Interim Afghan government. And finally, Beijing is well-positioned to protect its future investments in the Afghan economy through the BRI project.

China’s aggressive and assertive move into Russia’s traditional sphere of influence does not make the Kremlin nervous as much as the U.S. military presence in the region. China’s expansion of its military presence in Tajikistan was likely coordinated with Russia, which considers Central Asia to be its southern flank. Because Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan are part of the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) military alliance, opening a foreign military base in one of them requires the consent of this military block. The two most considerable regional powers, Russia and China, can be expected to pursue common counterterrorism strategies through the coordination and information-sharing on TIP Uyghur jihadists and Russian-speaking fighters based in Taliban-led Afghanistan.

The propaganda war between Communist China and Turkestan Islamic Party

As Beijing tries to fill the power vacuum left by the United States and expand its political and economic influence over the Afghan Taliban’s Interim Government, the veteran Uyghur jihadi group of Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP) and newly emerged Katibat al-Ghuraba al-Turkestani (KGT) are respectively intensifying their ideological war against China’s Communist regime.

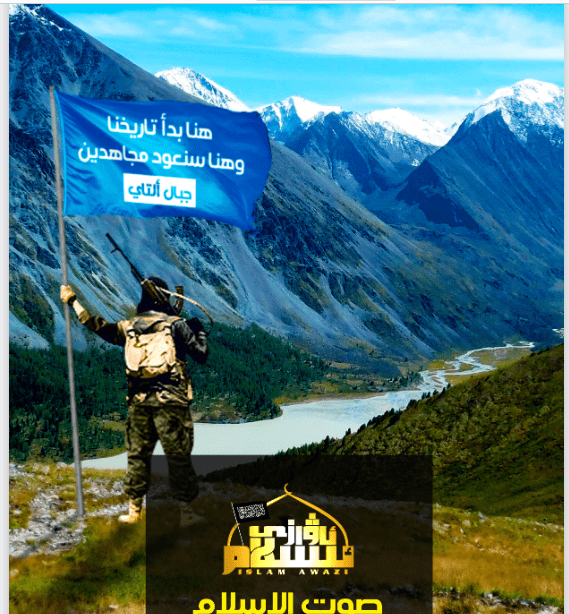

The media centre Islam Avazi (Voice of Islam), the TIP’s propaganda machine, systematically and vociferously criticises the Chinese Communist Government as “atheist occupiers” and “Chinese invaders” for occupying the lands of East Turkestan.19 Recently, the TIP’s main mouthpiece in its weekly radio program on the Uyghur-language website ‘Muhsinlar’20 stated that “China’s overseas military bases are evidence of its evil intentions to occupy new Islamic lands through creeping expansion.” Then the Uyghur speaker insists that:

“temporarily settling in new lands, the Chinese kafirs (disbeliever) will never leave there, a vivid example of which is the tragic experience of East Turkistan, whose religion, culture and history are Sinicized, and its titular Muslims are being brutally repressed.”

This research indicates that despite their long-standing involvement in the global jihad in Afghanistan and Syria and their strong alliances through oaths of allegiance (bayat) with al Qaeda, Taliban and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the central ideology of Uyghur Jihadists is the fight against the Chinese Communist regime.21 The strategic goal of the Turkestan Islamic Party is to liberate the historical lands of East Turkestan, now known as Xinjiang, from the occupation of the Chinese “communist infidels” and to build its state with shari’a rule there. In their regular statements, audios and videos, TIP propagandists raised the victimisation of Uyghur Muslims during China’s occupation of East Turkistan, which has long been a key theme in TIP’s ideological doctrine.

Amid establishing Chinese overseas military bases in Central Asia, TIP’s media centre Islam Avazi has sharply intensified anti-Beijing propaganda. Both the Taliban and TIP have double standards in this regard. Criticising the Chinese Communist regime, TIP deliberately avoids and never condemns the Taliban’s recent close ties with China. At the same time, when the Taliban recently criticised New Delhi for persecuting Muslims in Indian-administered Kashmir and called themselves defenders of the oppressed Muslim Ummah, they tried to sidestep the topic of China’s crackdown on Uyghurs in Xinjiang.22

Future of Uyghur Jihad in Post-American Afghanistan

Thus, even though the TIP remains an essential player of global jihad and a vanguard for the Uyghur cause, China’s pressure on the Taliban and its military bases in Central Asia will force Uyghur fighters to curb their jihadi ambitions in post-American Afghanistan. Undoubtedly, as before, the Taliban will continue their attempts to marginalise Central Asian jihadi groups in Afghanistan, making them utterly dependent on their will and exploiting them for their political purposes.

It is difficult to predict to what extent the Uyghur jihadists have the strength and patience to withstand Taliban moral pressure and Chinese Intelligence persecution in the new Afghanistan. Interestingly, researchers at the Newlines Institute claim the Taliban’s collaboration with Chinese military advisers present in Afghanistan.23 According to a senior source within the Taliban, “some 40 advisers from China (including some military ones) deployed to Afghanistan on October 3rd.” Therefore, it will be difficult for TIP to maintain its developed propaganda apparatus, to enhance its organisational capabilities in the new realities of Afghanistan when Chinese overseas military bases are breathing down its neck.

Beijing’s military footprint on the Af-Pak-China-Tajik border arena will force TIP to demonstrate its diplomatic and strategic ability in seeking support and solidarity from numerous umbrellas jihadi organisations such as al-Qaeda, Jalaluddin Haqqani’s Haqqani network, the Afghan and Pakistani Taliban, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), and even Islamic State in Khorasan (IS-K). Suppose al-Qaeda continues to weaken, and IS-K grows stronger via targeted attacks and successful recruitment. In that case, Central Asian jihadists may change their jihadi flag and join IS-K. The most capable defectors from al Qaeda to ISIS were Uzbek, Tajik and Uyghur foreign fighters in Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq, as their experience has shown.24

Any TIP’s move to take the jihad back to Xinjiang for its liberation, undoubtedly, will face steep odds. Beijing’s repressive security measures, such as high-tech mass surveillance and mass detention of Uyghurs in so-called re-education camps, have long deprived TIP of its network in Xinjiang.25 Worries that TIP is poised to ravage Xinjiang, therefore, seem overblown. With demographic changes in the Xinjiang region,26, where the Han population is almost the majority, the TIP has lost its social underpinning and perspective of waging jihad within the country.

Conclusion

In conclusion, wary of antagonising Beijing and its dependence on Chinese economic largesse, the Taliban Interim Government will progressively reduce its support for Uyghur jihadists. The establishment of Chinese military bases on the isthmus of the Wakhan Corridor and the strengthening of its anti-terrorism initiatives, combined with the monitoring of the Af-Pak-China-Tajik arena, call into question the extent to which TIP can conduct operations against China’s BRI.

Lastly, a rapprochement between China and the Taliban leaves TIP cornered, limiting room for manoeuvre and forcing some Uyghur Muhajireen (foreign fighters) to carry out a hijrah (migration) to Syria’s Idlib province to join their fellow tribesmen from Xinjiang. Nevertheless, despite this grim appraisal of TIP’s prospects in post-American Afghanistan, it can capitalise on its commitment to transnational jihad and expand its international network exploiting the Syrian melting pot. Indeed, given the physical remoteness from China’s overseas military bases, the Syrian quagmire will give the TIP a certain latitude, strengthening its ability to assert itself on the global jihad.

Sources

1Sheng, Yang; Fandi, Cui (2021) Taliban’s rapid victory embarrasses U.S., smashes image, arrogance, Global Times. Retrieved from: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202108/1231652.shtml (accessed 03/12/2021).

2China warns Taliban against Afghanistan again becoming ‘heaven’ for terror groups (2021), The Economic Times. Retrieved from: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/china-warns-taliban-against-afghanistan-again-becoming-haven-for-terror-groups/articleshow/85393743.cms?from=mdr (accessed 04/12/2021).

3Xin, Liu; Yunyi, Bai (2021) Wang Yi meets Afghan Taliban in Doha, yielding more positive remarks on fightingterrorism: experts, Global Times. Retrieved from: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202110/1237375.shtml (accessed 04/12/2021).

4Wenting, Xie; Yunyi, Bai (2021) Exclusive: New Afghan govt eyes exchanging visits with China; ETIM has no place in Afghanistan: Taliban spokesperson, Global Times. Retrieved from: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202109/1233876.shtml (accessed 04/12/2021).

5Will Afghan Taliban honor its promise to China to make clean break with ETIM? (2021), Global Times. Retrieved from: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202109/1234477.shtml (accessed 04/12/2021).

6Standish, Reid (2021) Taliban ‘Removing’ Uyghur Militants From Afghanistan’s Border With China, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved from: https://www.rferl.org/a/afghanistan-taliban-uyghurs-china/31494226.html (accessed 04/12/2021).

7Swaine, Michael D. (2010) China and the “AfPak” Issue, China Leaderhisp Monitor, No. 31, Carnegie Endownment. Retrieved from: https://carnegieendowment.org/files/CLM31MS.pdf (accessed 04/12/2021).

8Standish, Reid (2021) Beijing Cautiously Backs Taliban’s Hopes Of International Recognition In Afghanistan, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved from: https://gandhara.rferl.org/a/china-taliban-support/31480715.html (accessed 04/12/2021).

9China is our most important partner, says Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid (2021), WIONews. Retrieved from: https://www.wionews.com/south-asia/china-is-our-most-important-partner-says-taliban-spokesperson-zabihullah-mujahid-410510 (accessed 04/12/2021).

10Stone, Rupert (2019) The odd couple: China’s deepening relationship with the Taliban, TRT World. Retrieved from: https://www.trtworld.com/opinion/the-odd-couple-china-s-deepening-relationship-with-the-taliban-28712 (accessed 04/12/2021).

11King,Chris (2021) The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) And The Taliban Are ‘Old Friends’, MEMRI Daily Brief No. 319, The Middle East Media Research Institute. Retrievied from: https://www.memri.org/reports/chinese-communist-party-ccp-and-taliban-are-old-friends#_edn24 (accessed 04/12/2021).

12Topychkanov, Petr (2015) Secret Meeting Brings Taliban to China, Carnegie Moscow Center. Retrieved from: https://carnegiemoscow.org/2015/05/28/secret-meeting-brings-taliban-to-china-pub-60241 (accessed 04/12/2021); Jin, Wang (2016) What to Make of China’s Latest Meeting With the Taliban, The Diplomat. Retrievied from: https://thediplomat.com/2016/08/what-to-make-of-chinas-latest-meeting-with-the-taliban/ (accessed 04/12/2021).

13Felbab-Brown, Vanda (2020) A BRI(dge) too far: the unfulfilled promise and limitations of China’s involvement in Afghanistan, The Brookings Institution. Retrieved from: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/fp_20200615_china_afghanistan_felbab_brown.pdf (accessed 04/12/2021).

14Nebehay, Stephanie (2019), 1.5 million Muslims could be detained in China’s Xinjiang: academic, Reuters. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-xinjiang-rights/1-5-million-muslims-could-be-detained-in-chinas-xinjiang-academic-idUSKCN1QU2MQ (accessed 04/12/2021); “Break Their Lineage, Break Their Roots”. China’s Crimes against Humanity Targeting Uyghurs and Other Turkic Muslims (2019) Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/19/break-their-lineage-break-their-roots/chinas-crimes-against-humanity-targeting (accessed 04/12/2021).

15Bifolchi, Giuliano (2021) Chinese military base in Tajikistan: regional implications, Geopolitical Report Vol.12(13), SpecialEurasia. Retrieved from: https://www.specialeurasia.com/2021/10/28/chinese-military-base-in-tajikistan-regional-implications/ (accessed 04/12/2021).

16Shih, Gerry (2019) In Central Asia’s forbidding highlands, a quiet newcomer: Chinese troops, The Washington Post. Retreved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/in-central-asias-forbidding-highlands-a-quiet-newcomer-chinese-troops/2019/02/18/78d4a8d0-1e62-11e9-a759-2b8541bbbe20_story.html (accessed 06/12/2021).

17Putz, Catherine (2019) China in Tajikistan: New Report Claims Chinese Troops Patrol Large Swaths of the Afghan—Tajik Border, The Diplomat. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/in-central-asias-forbidding-highlands-a-quiet-newcomer-chinese-troops/2019/02/18/78d4a8d0-1e62-11e9-a759-2b8541bbbe20_story.html (accessed 06/12/2021); Umarov, Temur (2020) На пути к Pax Sinica: что несет Центральной Азии экспансия Китая (Towards Pax Sinica: What China’s Expansion brings to Central Asia), Carnegie Moscow Center. Retrieved from: https://carnegie.ru/commentary/81265#_edn1 (accessed 06/12/2021).

18Zhou, Zunyou (2016) China’s Comprehensive Counter-Terrorism Law, The Diplomat. Retrieved from: https://thediplomat.com/2016/01/chinas-comprehensive-counter-terrorism-law (accessed 06/12/2021).

19Botobekov, Uran (2017) Silk diplomacy of the Celestial Empire against the Turkistan Islamic Party, ModernDiplomacy. Retrieved from: https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2017/12/02/silk-diplomacy-of-the-celestial-empire-against-the-turkistan-islamic-party/ (accessed 06/12/2021).

21Botobekov, Uran (2017) China and the Turkestan Islamic Party: From Separatism to World Jihad, ModernDiplomacy. Retrieved from: https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2017/12/09/china-and-the-turkestan-islamic-party-from-separatism-to-world-jihad/ (accessed 06/12/2021).

22Khare, Vineet (2021) Afghanistan: Taliban says it will ‘raise voice for Kashmir Muslims’, BBC. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-58419719 (accessed 06/12/2021).

23Giustozzi, Antonio; Al Aqeedi, Rasha (2021) Security and Governance in the Taliban’s Emirate, Newlines Institute for Strategy and Policy. Retrieved from: https://newlinesinstitute.org/afghanistan/security-and-governance-in-the-talibans-emirate/ (accessed 06/12/2021).

24Botobekov, Uran (2021) Think Like Jihadist. Anatomy of Central Asian Salafi groups, Geopolitical Handbook No.09, ModernDiplomacy. Retrieved from: https://moderndiplomacy.eu/product/anatomy-of-central-asian-salafi-groups/ (accessed 06/12/2021).

25How Mass Surveillance Works in Xinjiang, China. ‘Reverse Engineering’ Police App Reveals Profiling and Monitoring Strategies (2019) Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/video-photos/interactive/2019/05/02/china-how-mass-surveillance-works-xinjiang (accessed 06/12/2021); Up to One Million Detained in China’s Mass “Re-Education” Drive (2018) Amnesty International. Retrieved from: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2018/09/china-up-to-one-million-detained/ (accessed 06/12/2021).

26Graphics: Demographic changes in Xinjiang over the years (2021) CGTN. Retrieved from: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-09-26/Graphics-Demographic-changes-in-Xinjiang-over-the-years-13RT0ZR9dg4/index.html (accessed 06/12/2021).