Geopolitical Report 2785-2598 Volume 13 Issue 7

Author: Riccardo Rossi

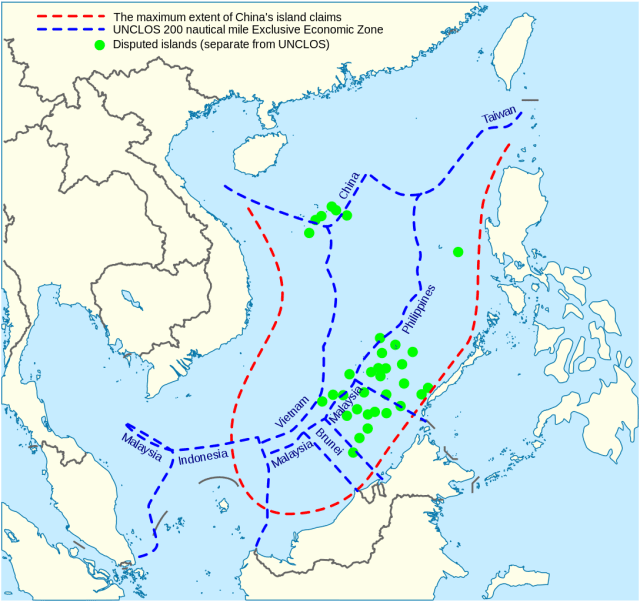

With the installation of Xi Jinping as head of state in 2012, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has identified the South China Sea as an area of high geopolitical importance for the pursuit of its geophysical peculiarities of specific political-strategic priorities.

These Chinese considerations for the South China Sea (SCS) have led to an increase in the presence of the People Liberation Army (PLA) within this geo-maritime area, particularly in the vicinity of the Spratly and Paracese archipelagos due to their proximity to the most strategically relevant areas of this semi-enclosed sea.

In the face of these considerations, the analysis aims to understand which the PRC considers areas of the SCS to be of distinct strategic interest and then evaluate how these affect the definition of the political-strategic priorities theorised by Beijing and the consequent military strategies.

The Chinese militarisation of the South China Sea

With the election of Xi Jining as Head of State in 2013, the People’s Republic of China embarked on a wide-ranging programme called ‘China Dream’, aimed at modernising the nation to put it in a position to increase its political and military influence in the geo-maritime area close to its coastal segment comprising the two sides of the East and the South China Sea, respectively bounded to the west by the Asian shoreline and to the east by the so-called first island chain comprising the Japanese archipelago, Taiwan and the Philippines.

Within this geo-maritime area, a good part of the political-military interests of the PRC is directed towards the South China Sea (SCS), due to the presence, within its waters, of certain zones held by Beijing to be of particular geostrategic importance, such as the straits of Luzon/Bashi and Malacca.

The attribution by the People’s Republic of China of high strategic importance to the areas mentioned above has represented a vital conditioning factor in the elaboration of its programme of militarisation for the SCS, mainly aimed at responding to two political-strategic needs.

The first foresees opposing the political-military presence of the United States, principally concentrated in the Philippine archipelago, where Washington has placed the largest bases in its possession. Among these, Beijing considers particularly dangerous the military zone of Antonio Bautista, situated near the Island of Palawan, where the U.S. Air Force has positioned the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile system, which can strike targets localised both along its coastline and some of the artificial islands which it has built in the Spratly Archipelago.

The second political-strategic priority recognised by the People’s Republic of China for the South China Sea is the supervision of the areas it considers most strategically valuable, such as the Straits of Malacca and Luzon/Bashi.

There are two main reasons for Beijing to focus its attention on Malacca and Luzon. The first includes the fact that Bashi and Malacca represent the two most extensive entry and exit points from the SCS, from which it follows that their mastery allows controlling the main lines of maritime communication that cross this semi-closed sea. The second reason, specifically Luzon, represents a strait of particular strategic importance for the PRC. Its possible control would allow direct access to the open Pacific, thus bypassing the obstacle to the north represented by the Japanese island territories, specifically the Miyako channel.

The attribution by Beijing of high geostrategic importance to the Straits of Malacca and Bashi has led the Xi Presidency, in a joint agreement with the People’s Liberation Army, to elaborate a strategic-military doctrine aimed at increasing its presence in the areas closest to them, such as its southern shoreline, the Island of Hainan, and the archipelagos of Spratly and Paracelsus. Among these three areas, the geo-maritime space comprised between the southern Chinese coastline and the island of Hainan represents, for Xi Jinping, a single geostrategic space, the tactical-military importance of which is ascribable to the frontal position of the Laizhou peninsula towards Hainan, which is, in turn, remarkable for its proximity to the archipelagos of the Paracelsus and the Spratlys. The combination of these positions led the People’s Republic of China to establish a military command for the South China Sea that would encompass all branches of the armed forces.

Among the various components of the Chinese defence instrument, it is worth mentioning the importance of the PLA Navy in carrying out maritime patrol operations in the SCS, guaranteed by the presence of two essential bases. The first is Zhanjiang, located at the southern tip of the Laizhou peninsula and the headquarters of the South Sea Fleet, where, according to the U.S. Department of Defense, an aircraft carrier, nuclear attack submarines, ballistic missile launchers, DF 21 mobile missile batteries and HQ-9 SAM medium-range surface batteries are located. The second is the military outpost of Yulin, built on the island of Hainan, which houses part of the Jin-class SSBN submarines, and in recent years has undergone substantial expansion works to satisfy a twofold tactical-strategic need. On the one hand, to favour the increase of the submarine nuclear flotilla; on the other, its position close to the Paracel and Spratly islands has allowed the PLA to expand or construct artificial military installations in these two archipelagos, including radar systems, hangars, aircraft and missile and artillery defence equipment.

Within the Paracelsus archipelago, the artificial island of Woody Island, due to its proximity to Hainan, is considered by Beijing as a fundamental strategic hub connecting the military area of Yulin and the artificial maritime bases located in the Spratlys. In this sense, in recent years, Woody has been enhanced by the PLA through the deployment of personnel, J-11 fighter jets and JH-7 fighter bombers, radar detection systems, ISR instrumentation and DF-21 6carrier-killer missiles.

In the Spratly archipelago, the People’s Republic of China has built two types of artificial islands. The first ones of great dimensions include Fiery Cross Reef, Subi Reef, Mischief Reef, among them accumulated for landing strips for aircraft, Hangers, land artillery, radar and sensors. Among these islands, satellite photos show the presence of a Z-8 helicopter and two Y-8 and Y-9 aircraft7 at the 3750-metre long landing strip of Fiery Cross Reef. In addition, there is a second category of artificial islands, including Johnson South Reef, Hughes Reef, Cuarteron Reef, and Gaven Reefs, smaller platforms that do not have a runway for fixed-wing aircraft but are equipped with radar, land artillery, SAM missile systems, and landing areas for light and heavy helicopters8.

The construction of these artificial islands in the South China Sea by the PRC is a central element in increasing the range of its armed forces in the vicinity of the Philippines and the waters of the Luzon and Malacca Straits.

Conclusions

In these conclusions, an attempt will be made to summarise why the People’s Republic of China considers the South China Sea a rank area of geostrategic importance to protect its national interests.

The first observation supporting this consideration is ascribable to the particular perception of Beijing of the SCS as a non-homogenous geopolitical space from the moment in which it recognises the existence of certain areas strategically more important than others, identified in the maritime straits of Luzon/Bashi and Malacca.

This particular assessment of Beijing has been a factor of high incidence in the definition of its political-strategic objectives for the South China Sea, identified in countering the military presence of the United States and overseeing the geo-maritime space adjacent to Malacca and Luzon.

The definition and the Chinese attempt to pursue the objectives as mentioned above has required the Xi Jinping administration, in a joint agreement with the PLA leadership, to develop a political-military doctrine aimed at increasing the number of its war assets in its territories near Luzon and Malacca, such as the Laizhou Peninsula, the Island of Hainan and the archipelagos of Spratly and Paracelsus.

This decision by Beijing to increase its military presence in the areas presented above represents, for the Xi Presidency, a necessary decision to improve the operational capabilities of the PLA and PLN in carrying out patrol operations and air-naval raids in the vicinity of the Straits of Malacca, Luzon and the Philippines, but at the same time to establish its sea control in the waters of Luzon and Malacca in the medium-long term, in order to deny access to the air force and the U.S. Seventh Fleet stationed in Yokosuka to the geo-maritime space of the South China Sea.

Therefore, the will of the People’s Republic of China to impose its sea control in the SCS will lead, in the next decade, to a constant increase in the military assets of the PLA in these geo-maritime areas because the Xi Jinping administration considers them as the strategy to pursue in order to respond to and break the U.S. policy of the Pivot to Asia aimed at limiting the political-economic rise within the China Sea and in the Indo-Pacific region.